An analysis of attitudes and spending reveals a return to traditional values, driven by consumers searching for quality, affordability, and connection.

The wave of hyper-consumerism that propelled the U.S. economy through the last decades of the 20th century and into the first years of the 21st century has passed. Say good-bye to all the signs of easy wealth we knew from the recent past: McMansions, SUVs, and recreational shopping. Consumer spending patterns are changing as part of a trend that has been quietly gathering strength over the past 10 years. Say hello to a lifestyle more focused on community, connection, quality, and creativity. People are returning to old-fashioned values to build new lives of purpose and connection. They also realize that how they spend their money is a form of power, and are moving from mindless consumption to mindful consumption, increasingly taking care to purchase goods and services from sellers that meet their standards and reflect their values.

This change in consumer attitudes — visible not only in the United States but also in other countries affected by the Great Recession — is not a fad or whim. It is, in part, a reaction to economic hard times. But it is also closely related to the civic dissatisfaction that is rocking the political establishment, and additionally has some roots in environmental awareness and changing aspirations. That is why this Spend Shift movement, as we call it, is here to stay. It will create opportunities for businesses that heed its message, and penalize those that do not. (For another perspective, see "Values vs. Value," by Timothy Devinney, Pat Auger, and Giana M. Eckhardt, s+b, Spring 2011.)

Our view of the Spend Shift is based on two years of gathering and analyzing data, and traveling around the U.S. to discover how the recession has affected people's lives. We started with Young & Rubicam's BrandAsset Valuator (BAV), which is a poll of consumer values, attitudes, and shopping behaviors that goes back nearly 20 years. (Although the data sample we focus on in this article is from the U.S., we found that there are similar dynamics in Europe and other industrialized countries.) The BAV holds data on more than 40,000 brands in more than 50 countries, and every quarter it is supplemented with new results — on purchasing and social attitudes — from 16,000 respondents in the U.S. alone. In all, we have queried more than a million consumers in 50 countries on some 70 brand metrics, which include the general awareness consumers have of a brand, the particular ways it makes them feel, and many others. (See "The Trouble with Brands," by John Gerzema and Ed Lebar, s+b, Summer 2009.)

The BAV data revealed that even before the recession took hold in mid-2008, there were dramatic shifts in what people expected in the consumer marketplace and how they defined and pursued what they considered the good life. As a factor in decision making, sheer desire for the goods themselves has been declining sharply for the past decade. More recently, the BAV surveys show sharp increases in the number of consumers who want positive relationships with marketplace vendors and who focus more on corporate behavior. Between 2005 and 2009, a growing number of people rejected status-driven values such as snobbishness and exclusivity, and embraced attributes related to bringing people closer together or making the world a better place. Among the once-prized brand attributes that declined in this period were: "exclusive" (down 60 percent), "arrogant" (down 41 percent), "sensuous" (down 30 percent), and "daring" (down 20 percent). On the opposite side of the scale, the brand attributes Americans found more important as they began to sense the impending recession and then suffered through the crisis were: "kindness and empathy" (up 391 percent), "friendly" (up 148 percent), "high quality" (up 124 percent), and "socially responsible" (up 63 percent).

The reference to "kindness" is not a typo. Between 2005 and 2009, U.S. consumers expressed a nearly fourfold increase in their preference for companies, brands, and products that show kindness in both their operations and their encounters with customers. This desire for companies to be more empathetic toward consumers is the biggest shift in any attitude that we have ever seen during the BAV survey's two-decade history.

The BAV data told us that at the grass roots, people were well ahead of the pundits, corporations, and political leaders. Some of the most important economic statistics supporting this trend come from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis reports on personal savings. The reports show that ordinary Americans began raising their deposits in savings accounts and other secure investments a full two years before the start of the recession. Even as unemployment surged past 10 percent, U.S. consumers socked away more money every month. By the middle of 2009, people were saving about 7 percent of their disposable income — a figure that hadn't been seen since 1995. We also know that people cut back on spending many months before the recession began. In fact, Americans reduced consumption so sharply that in the middle of 2008, it dropped below their disposable income and just kept falling. This reversal of earlier trends in saving and spending continued throughout all of 2009. Without being scolded, lectured, or led from above, U.S. consumers had quietly changed their behavior.

Regardless of companies' size or their target market, they must understand the significance of the Spend Shift to compete in the post-recession economy. From the scores of interviews we conducted and thousands of data points we accumulated, we can identify a wide array of ways that the shift in attitudes, values, expectations, and behaviors will change the way we buy, sell, and live. We have distilled our findings into four defining principles that together offer a comprehensive look at the origins and impacts of the Spend Shift.

1. United by Change

The Spend Shift is a far-reaching and inclusive phenomenon that can't be defined by any particular demographic. According to our data, 55 percent of all Americans are part of this movement; in addition, about one-quarter of the U.S. adult population embraces many of the Spend Shift attitudes and characteristics (we call them Fast Followers). Although the word values tends to polarize U.S. citizens, the Spend Shift is blind to geography, education, age, and income.

Spend Shifters can be found across the nation: 17 percent are in the Northeast, 23 percent are in the Midwest, 36 percent are in the South, and 24 percent are in the West. Although we'll limit our discussion to what's happening in the U.S., it is worth noting that the BAV data shows that the Spend Shift is a global trend. For example, we found that 53 percent of French consumers are Spend Shifters, as are 45 percent of German and Italian consumers.

Members of the movement have varying education backgrounds: 23 percent have a high school diploma, 21 percent have a college degree, and 11 percent have completed postgraduate studies. Spend Shifters also represent diverse income brackets; for example, 28 percent earn less than US$40,000 a year, but 18 percent earn between $75,000 and $100,000. They represent Republicans, Democrats, and Independents (28, 31, and 41 percent, respectively). Millennials (the generation born between 1980 and 1995) lead the movement, with 58 percent of 22- to 28-year-olds participating, yet nearly half of all seniors belong, too (including 55 percent of adults age 68 and above).

What unites all these Spend Shifters is a common sense of optimism and newfound purpose. As the shock of economic loss wears off for many people, they are redefining what it means to be successful and happy. They are living with less and yet feeling greater satisfaction. Seventy-eight percent of those surveyed reported they are happier with a more back-to-basics lifestyle. Eighty-eight percent reported they buy less-expensive brands than they used to.

2. The New Thrift

Prior to the Great Recession, the American dream was defined by largeness and acquisition. Yet as a result of the crisis and its lingering presence in the economy, more than two-thirds of U.S. respondents to our survey now prefer a pared-down lifestyle with fewer possessions and less emphasis on displays of wealth. (The figure rises to 77 percent among millennials.)

Consumer spending will no longer be able to grow faster than personal income, as it did during the 30 years leading up to the crisis. Greater savings coupled with less borrowing is not a value that is foreign to Americans. We would argue this is not a "new normal," but an old one: If you look at historical savings rates in the U.S., people have on average saved 10 percent of their income going back as far as six decades. It was only in the mid-1980s that availability and promotion of consumer credit, as well as sustained economic growth, first encouraged ordinary people to get out over their skis. In only 20 years, average American households swung from being net savers to being net borrowers. Now, however, consumers are returning to traditional values that have long defined the U.S. ideal.

In the same vein, people want to do more on their own. In the post-recession economy, resourcefulness and self-sufficiency are viewed as virtues, and excessive consumption as a sign of weakness. In our surveys, 84 percent agreed with the following statement: "These days I feel more in control when I do things myself instead of relying on others to do them for me." We examined the 2009 performance of a basket of "retooling" companies — those that are in the top 10 percent of our data on being "helpful," "reliable," "educational," and "durable," such as LeapFrog, Weight Watchers, Craftsman, and DeWalt, because they help people help themselves. The performance of these companies against all others is notable: They performed 249 percent better than other companies when respondents were asked whether they would recommend these brands to a friend, 234 percent better when respondents were asked if they used the products regularly, and 210 percent better on whether the products were worth a premium price.

Instead of seeking status through acquisition, many people, we discovered, are seeking ways to experience a sense of competence, self-sufficiency, and accomplishment. Look, for example, at Etsy.com, a craft and vintage item website that serves as a retail and trading marketplace for millions. Beginning in 2005, Etsy founder Rob Kalin and his partners began developing an online place where any artisan could display work and sell to any buyer in the world. Within five years, Etsy had 300,000 vendors — the majority were women in their 20s and 30s — the site was visited by millions of shoppers every month, and the company grew to be worth an estimated $300 million in 2010. Etsy's mission resonates in today's marketplace: "to enable people to make a living making things." If you have an idea for helping people learn new skills and connect with others, your business has a good chance of success.

3. Transparency Breeds Trust

Today the buying public is savvy about marketing, search, and social media. Companies serving these customers, who know more and expect more, will need to continuously listen, respond, and innovate. They are in for a challenge: Our data shows that confidence in all types of big organizations, including big government and big business, has declined by nearly 50 percent in the past two years. Consumer confidence has dropped especially in the financial and automotive sectors, but also in retail, packaged goods, consumer electronics, and 20 other product and service categories.

Wary consumers are going beyond just reading labels to get the best products and the best deals. The most tech-savvy are using online services as they stand in the supermarket aisle to get instant access to information on prices and on a company's social or environmental record. GoodGuide, for example, a California company that tracks, tests, and publishes research on the basic "goodness" of products people buy, has reviewed more than 65,000 products and posted findings online for consumers since 1997. Shoppers are also relying on one another for information, via Facebook, Twitter, and online rankings.

Twentieth-century companies were in the information arbitrage business. They knew more about their product than customers did, and they used that information advantage to create profits. Today, however, customers have equal (and sometimes superior) access to data. As a result, transparency becomes all the more crucial. Today's stakeholders can see through a glossy cover-up. They crave a true, authentic story. They will be interested in how a company thinks and how it makes decisions.

One company that has recognized this is Patagonia Inc., evident by its launch of the Footprint Chronicles in late 2007. This online feature reveals how the manufacturing and delivery of Patagonia's products affect the environment. A visitor to the site can click on any product and track its environmental and social impact along its path to the store. As a product crisscrosses the globe, pop-up videos explain each stage of production, from design creation to sewing to distribution, giving statistics for each item's energy consumption, distance traveled, carbon emissions, and waste generated. Although the Footprint Chronicles have demonstrated that some Patagonia products have negative environmental impacts that are nearly impossible to upend, the company's presentation of fact rather than message has helped establish it as an honest, trustworthy company. In today's marketplace, successful companies will practice complete transparency, letting customers see their supply chains, management strategies, and values.

4. Companies That Care

As we noted earlier, our data suggests that kindness and empathy are now dominant discriminators in commerce, and are valuable attributes of the best companies. The ability of a company to identify with its customers is now a prerequisite for any brand in the post-crisis age. Today, openness, humility, and understanding are critical. Generosity binds a company to its community and its stakeholders.

The rising importance of generosity reflects the fact that the post-crisis era will be defined by inclusion rather than exclusion. The emphasis is on being more human and humane in transactions with others, and people will set these same standards for the businesses with which they deal. Spend Shifters are buying artisanal food because they trust companies that reveal how their food is produced and handled. They patronize cooperative small businesses because such businesses use their profits to build up their local regions. Passionate customer groups will also band together to fund niche offerings that speak directly to the areas about which they feel most strongly. Because 71 percent of U.S. consumers are now aligning their spending with their values, businesses that practice in a new way will find a vibrant marketplace. Instead of selling shoes, such businesses sell empathy and respect. For each pair of Toms Shoes that a customer buys, for example, the company sends a pair to a child in the developing world. Instead of serving food, companies create communities of hope. Instead of making cars, they promise fairness, openness, and shared discourse.

Consumers will be looking for signs that companies care about their impact on communities and are investing in making things better. Selling to your customers will require investing in your customers. Generosity opens up networks, provides access to talent pools, and creates future customers. The vanguard companies understand that showing kindness and humanity is now a competitive advantage.

Microsoft is a telling example. Although Apple's ads make it seem as though all the cool kids hate Microsoft and favor Apple, the two companies aren't even close when it comes to the sentiments of the public at large. In our BAV survey, Microsoft always scores high on measures of its reputation, exceeding Apple by a wide margin. How does Microsoft do it? Despite its massive size, Microsoft is still widely associated with the single personality of its founder, Bill Gates. He gives Microsoft a human face and, more important, his philanthropy gives the company a heart. In February 2009, Microsoft launched a program called Elevate America to provide 2 million people with free training in information technology to help them find jobs in the postindustrial economy. By August 2010, Elevate America was running in more than 30 states and serving 900,000 people.

When we talked to Akhtar Badshah, Microsoft's senior director of global community affairs, he told us that in its response to the recession, Microsoft pursued three main areas of focus: education, innovation, and jobs and economic opportunity. Those choices are good for Microsoft, because they create an opportunity for the company to demonstrate its strengths to current and future customers. The key point is that Microsoft uses both its money and its true areas of expertise to maximize the good it can do as a citizen corporation, showing how a company can be charitable by redeploying its existing assets and infrastructure as tools for social and economic development.

The Consumer Connection

The Conference Board's Consumer Confidence Index was at 50.2 in October 2010, up from an all-time low of 25.3 in February 2009, but still far from 90, the indicator of a stable economy. (In May 2000, it reached a high of 144.7.) Although the growth of consumer spending appears to be slowing, we believe that people are simply reallocating the way they spend — looking for a connection to the creator of the product; banding together to get better deals; and pushing service and product creators to do more, price better, and connect more deeply to their wants and needs.

Even as people find themselves less rich, they are deploying their dollars in a more calculated and strategic way to influence institutions such as corporations and government. This desire to use money to express values stands out in our BAV data, and was expressed by many of the people with whom we spoke. Nearly two-thirds of all the people who responded to the BAV felt they could affect corporate behavior through their purchasing habits, and the same proportion avoided companies whose values contradicted their own.

The most successful companies will respond to this shift by adopting a business model in which all three parties — the business, the customer, and the community — win in every transaction. Although the Spend Shift will dampen domestic demand for some products, the market for values-oriented goods and services offers opportunities for growth in what might otherwise be considered mature categories. We examined the performance of a group of companies and brands that scored in the top 20 percent in the BAV survey on the values we had noted were becoming increasingly important — self-reliance, adaptability, honesty, quality, and community. And we found that in aggregate they enjoyed nearly three times as much usage and preference as brands that did not represent these values.

We believe that the future face of capitalism will be defined by delivering value and values. Those that embrace this reality and adapt will find extraordinary opportunities. Those that ignore it will do so at their peril.

Author Profile:

Thanks to Strategy+Business

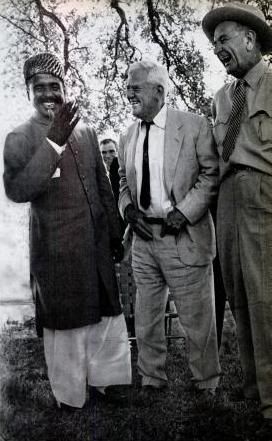

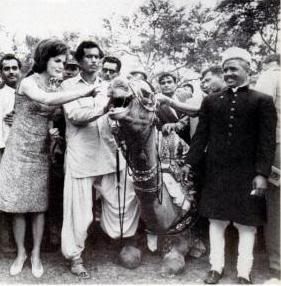

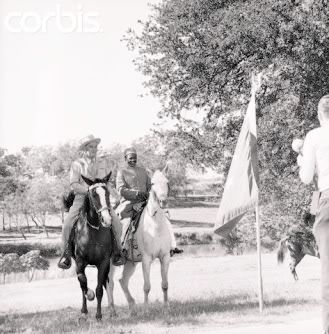

All these people were there to receive Lyndon Baines Johnson, Vice President of the United States Of America who was due to land any moment in Pakistan. LBJ was on a good will tour and his itinerary included a tour of our then capital city, Karachi followed by Lahore and Peshawar.

All these people were there to receive Lyndon Baines Johnson, Vice President of the United States Of America who was due to land any moment in Pakistan. LBJ was on a good will tour and his itinerary included a tour of our then capital city, Karachi followed by Lahore and Peshawar.  Then of course there were cars like Dodge Dart and Chevy Bel-Air carrying Govt and U.S.Embassy officials. The whole motorcade took route of main Drigh Road (now Shahrah-e-Faisal) for the President's House (now Sindh Governor House — we lived in the President's Estate adjacent to the President's House and Shaikh Habibur Rahman Uncle was our wall-to-wall neighbor in that 1912 one story buyilding which now houses Surveyor General of Pakistan's Office).

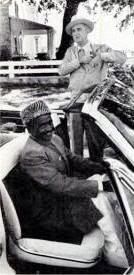

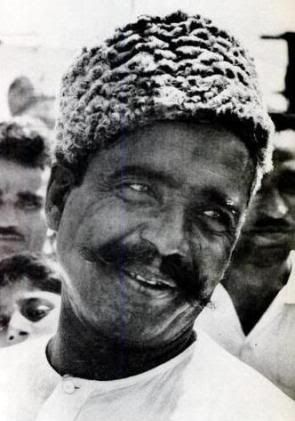

Then of course there were cars like Dodge Dart and Chevy Bel-Air carrying Govt and U.S.Embassy officials. The whole motorcade took route of main Drigh Road (now Shahrah-e-Faisal) for the President's House (now Sindh Governor House — we lived in the President's Estate adjacent to the President's House and Shaikh Habibur Rahman Uncle was our wall-to-wall neighbor in that 1912 one story buyilding which now houses Surveyor General of Pakistan's Office).  With Police Motorbikes speeding in line and blowing whistles and siren occassionally ahead of the motorcade…the journey progressed smoothly till something happened !!! Driver Ishaq applied brakes smoothly–good enough not to make the car behind hit the Presidential Car. All the followers literally ran towards the Presidential Cadillac fearing that something awful has happened to either of the two VVVIPs in that car when out came Vice President Johnson with President Ayub. They slowly walked towards the site left of Drigh Road at the exact spot where currently stands the Finance and Trade Centre (FTC). On that day however, a 38 year old camel cart owner (Sar'eban) Bashir Ahmed was standing there. He was cladfed in shalwar kameez full of dust and stood shivering next to his camel cart with DIG police Mian Bashir Ahmed (he had the same name as the camel man Bashir Ahmed) consoling him to remain calm.

With Police Motorbikes speeding in line and blowing whistles and siren occassionally ahead of the motorcade…the journey progressed smoothly till something happened !!! Driver Ishaq applied brakes smoothly–good enough not to make the car behind hit the Presidential Car. All the followers literally ran towards the Presidential Cadillac fearing that something awful has happened to either of the two VVVIPs in that car when out came Vice President Johnson with President Ayub. They slowly walked towards the site left of Drigh Road at the exact spot where currently stands the Finance and Trade Centre (FTC). On that day however, a 38 year old camel cart owner (Sar'eban) Bashir Ahmed was standing there. He was cladfed in shalwar kameez full of dust and stood shivering next to his camel cart with DIG police Mian Bashir Ahmed (he had the same name as the camel man Bashir Ahmed) consoling him to remain calm. Ten days later, two officials from the U.S.Embassy and two officials from the President of Pakistan's Secretariat visited Bashir Ahmed at his residence in Lyari (Bashir was a Makrani) for arranging his passport and U.S.Visa. Government of Pakistan got him three sets of sherwanis, a white shalwar-kameez and Jinnah caps from Jalal Din & Sons in Saddar and Rahman Hat Villa near Paradise Cinema with some Onyx products as gift from Bashir to LBJ. Within a week this Pakistani Camel Cart owner from Lyari, Karachi flew to New York by Pan American Clipper Jet Boeing 707 where he was received by LBJ aide. The next 12 days of Bashir were spent in New York, Washington DC and Dallas at the personal ranch of LBJ where his daughter Tricia and Ladybird Johnson held Bar-B-Q party, luncheon and breakfast gathering in honor of Vice President of United States of America Lyndon Baines Johnson's Pakistani friend Camel Cart owner (Sar'eban) Bashir Ahmed. Later Bashir returned home blessed with some worthwhile gifts which included a Mack Truck and a American bicycle for his son and some financial package to start a more elevated business.

Ten days later, two officials from the U.S.Embassy and two officials from the President of Pakistan's Secretariat visited Bashir Ahmed at his residence in Lyari (Bashir was a Makrani) for arranging his passport and U.S.Visa. Government of Pakistan got him three sets of sherwanis, a white shalwar-kameez and Jinnah caps from Jalal Din & Sons in Saddar and Rahman Hat Villa near Paradise Cinema with some Onyx products as gift from Bashir to LBJ. Within a week this Pakistani Camel Cart owner from Lyari, Karachi flew to New York by Pan American Clipper Jet Boeing 707 where he was received by LBJ aide. The next 12 days of Bashir were spent in New York, Washington DC and Dallas at the personal ranch of LBJ where his daughter Tricia and Ladybird Johnson held Bar-B-Q party, luncheon and breakfast gathering in honor of Vice President of United States of America Lyndon Baines Johnson's Pakistani friend Camel Cart owner (Sar'eban) Bashir Ahmed. Later Bashir returned home blessed with some worthwhile gifts which included a Mack Truck and a American bicycle for his son and some financial package to start a more elevated business.

In 1972-73 when Zia Moheyuddin started his famous Zia Show by recording it before a live audience at the Fleet Club-Karachi auditorium near Lucky Star-Saddar, I was attached with Zia Bhai as his unaccredited Manager. I was then a young banker at HBL Nursery Branch, PECHS and I took pride in marketing the prize account of Zia Moheyuddin and provided home-service for his banking transactions like picking up his PTV cheques and arranging statements etc. At time I also acted as a chapperone to him at several shows he recorded there.

In 1972-73 when Zia Moheyuddin started his famous Zia Show by recording it before a live audience at the Fleet Club-Karachi auditorium near Lucky Star-Saddar, I was attached with Zia Bhai as his unaccredited Manager. I was then a young banker at HBL Nursery Branch, PECHS and I took pride in marketing the prize account of Zia Moheyuddin and provided home-service for his banking transactions like picking up his PTV cheques and arranging statements etc. At time I also acted as a chapperone to him at several shows he recorded there.  The United States is in the middle of a devastating long-term economic decline and it is getting really hard to deny it. Over the past year I have included literally thousands of depressing statistics in my articles about the U.S. economy. I have done this in order to make an overwhelming case that the U.S. economy is in deep decline and is dying a little bit more every single day. Until we understand exactly how bad our problems are we will never be willing to accept the solutions. The truth is that our leaders have absolutely wrecked the greatest economic machine that the world has ever seen. Most Americans just assume that we will always experience overwhelming prosperity, but that is not anywhere close to the truth. We are not guaranteed anything. Our manufacturing base has been gutted, the number of jobs is declining, more Americans are dependent on government handouts than ever before, our dollar is dying and as a nation we are absolutely drowning in debt. The economists that are trumpeting an "economic recovery" and that are declaring that the U.S. economy will soon be "better than ever" are delusional. We really are steamrolling toward a complete and total economic collapse and our leaders are doing nothing to stop it.

The United States is in the middle of a devastating long-term economic decline and it is getting really hard to deny it. Over the past year I have included literally thousands of depressing statistics in my articles about the U.S. economy. I have done this in order to make an overwhelming case that the U.S. economy is in deep decline and is dying a little bit more every single day. Until we understand exactly how bad our problems are we will never be willing to accept the solutions. The truth is that our leaders have absolutely wrecked the greatest economic machine that the world has ever seen. Most Americans just assume that we will always experience overwhelming prosperity, but that is not anywhere close to the truth. We are not guaranteed anything. Our manufacturing base has been gutted, the number of jobs is declining, more Americans are dependent on government handouts than ever before, our dollar is dying and as a nation we are absolutely drowning in debt. The economists that are trumpeting an "economic recovery" and that are declaring that the U.S. economy will soon be "better than ever" are delusional. We really are steamrolling toward a complete and total economic collapse and our leaders are doing nothing to stop it.