Saturday, March 19, 2011

Quote By Einstein

Record-Breaking 2010 Eastern European/Russian Heatwave

ScienceDaily (Mar. 18, 2011) — An international research team involving ETH Zurich has compared the hot summers of 2003 and 2010 in detail for the first time. Last year's heatwave across Eastern Europe and Russia was unprecedented in every respect: Europe has never experienced so large summer temperature anomalies in the last 500 years.

The summer of 2010 was extreme. Russia was especially hard hit by the extraordinary heat: in Moscow, daytime temperatures of 38.2°C were recorded and it didn't get much cooler at night. Devastating fires caused by the dry conditions covered an area of 1 million hectares, causing crop failures of around 25%; the total damage ran to about USD 15 billion. Even though passengers were also collapsing on trains in Germany in 2010 because the air-con units had failed in the heat, the general perception is still that the summer of 2003 was the most extreme -- among Western Europeans at least. An international research team involving ETH Zurich has now compared the two heatwaves and just published their findings in Science.

Area fifty times bigger than Switzerland

The 2010 heatwave shattered all the records both in terms of the deviation from the average temperatures and its spatial extent. The temperatures -- depending on the time period considered -- were between 6.7°C and 13.3°C above the average. The heatwave covered around 2 million km2 -- an area fifty times the size of Switzerland. On average, the summer of 2010 was 0.2°C warmer in the whole of Europe than in 2003. Although it might not sound like much, it's actually a lot when calculated over the vast area and the whole season. "The reason we felt 2003 was more extreme is that Western Europe was more affected by the 2003 heatwave and it stayed warm for a long period of time," explains Erich Fischer, a postdoc at the Institute for Atmospheric and Climate Science at ETH Zurich.

The reason for the heatwaves in both 2003 and 2010 was a large, persistent high-pressure system associated by areas of low pressure in the east and west. In 2010 the heart of this high-pressure anomaly, often referred to as blocking, was above Russia. The low pressure system to the east was partly responsible for the floods in Pakistan. But the blocking was not the only reason for the extraordinary heat between July and mid-August; on top of that, there was little rainfall and an early snow melt, which dried out the soil and aggravated the situation. "Such prolonged blockings in the summertime are rare, but they may occur through natural variability. Therefore, it's interesting for us to put the two heatwaves in a wider temporal perspective," explains Fischer.

500-year-old temperature record broken

With this in mind, the researchers compared the latest heatwaves with data from previous centuries. Average daily temperatures are available back as far as 1871. For any earlier than that, the researchers used seasonal reconstructions derived from tree rings, ice cores and historical documents from archives. The summers of 2003 and 2010 broke 500-year-old records across half of Europe. Fischer stresses: "You can't attribute isolated events like the heatwaves of 2003 or 2010 to climate change. That said, it's remarkable that these two record summers and three more very hot ones all happened in the last decade. The clustering of record heatwaves within a single decade does make you stop and think."

More frequent and intense heatwaves

In order to find out whether such extreme weather conditions could become more common in future, the researchers analysed regional scenarios for the periods 2020-2049 and 2070-2099 based on eleven high-resolution climate models and came up with two projections: the 2010 heatwave was so extreme that analogues will remain unusual within the next few decades. At the end of the century, however, the models project a 2010-type heatwave every eight years on average. According to the researchers, by the end of the century heatwaves like 2003 will virtually have become the norm, meaning they could occur every two years. While the exact changes in frequency depend strongly on the model, all the simulations show that the heat waves will become more frequent, more intense and longer lasting in future.

Story Source: The above story is reprinted (with editorial adaptations by ScienceDaily staff) from materials provided by ETH Zürich.

'Bilingual' Neurons May Reveal The Secrets Of Brain Disease

ScienceDaily (Mar. 18, 2011) — A team of researchers from the University of Montreal and McGill University have discovered a type of "cellular bilingualism" -- a phenomenon that allows a single neuron to use two different methods of communication to exchange information. "Our work could facilitate the identification of mechanisms that disrupt the function of dopaminergic, serotonergic and cholinergic neurons in diseases such as schizophrenia, Parkinson's and depression," wrote Dr. Louis-Eric Trudeau of the University of Montreal's Department of Pharmacology and Dr. Salah El Mestikawy, a researcher at the Douglas Mental Health University Institute and professor at McGill's Department of Psychiatry.

An overview of this discovery was published in the Nature Reviews Neuroscience journal.

Their results show that many neurons in the brain are able to control cerebral activity by simultaneously using two chemical messengers or neurotransmitters. This mode of communication is known as "cotransmission." According to Dr. Trudeau, "the neurons in the nervous system -- both in the brain and in the peripheral nervous system -- are typically classified by the main transmitter they use." For example, dopaminergic neurons use dopamine as a transmitter to communicate important information for many different phenomena such as motivation and learning. The malfunction of these neurons is involved in serious brain diseases such as schizophrenia and Parkinson's. "Our recent research, carried out in part with Dr. Laurent Descarries at the University of Montreal, shows that dopaminergic neurons use glutamate as a second transmitter. That means they are able to transmit two types of messages in the brain, on two time scales: a fast one for glutamate and a slower one for dopamine."

Other research conducted by Dr. Salah El Mestikawy's team at the Douglas Mental Health University Institute observed the same kind of bilingualism in brain neurons that use serotonin, a group of cells that communicate important information for controlling mood, aggression, impulsivity and food intake, and also those that use acetylcholine, an important messenger for motor skills and memory that is unbalanced by Parkinson's disease, antipsychotic drugs and in drug addiction.

Joint studies carried out with their colleague Dr. Åsa Wallen-Mackenzie at Uppsala University in Sweden and published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal suggest that the secretion of glutamate by dopaminergic neurons could, for example, be involved in the behavioural effects of psychostimulants such as amphetamines and cocaine. "We know very little about the role of cotransmission in disease and the regulation of behaviour, however," Dr. Trudeau warned. "That will have to be the subject of future studies."

The studies were funded by grants from the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education and the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (France).

Story Source: The above story is reprinted (with editorial adaptations by ScienceDaily staff) from materials provided by University of Montreal.

Robert de LaSalle (November 21, 1643 – March 19, 1687)

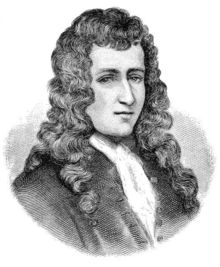

| René-Robert Cavelier | |

|---|---|

A 19th-century engraving of Cavelier de La Salle | |

| Born | November 21, 1643 Rouen, Normandy, France |

| Died | March 19, 1686 (aged 42) present day Huntsville, Texas |

| Nationality | French |

| Occupation | explorer |

| Known for | exploring the Great Lakes, Mississippi River, and the Gulf of Mexico |

| Signature | |

| |

René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, or Robert de LaSalle (November 21, 1643 – March 19, 1687) was a French explorer. He explored the Great Lakes region of the United States and Canada, the Mississippi River, and the Gulf of Mexico. La Salle claimed the entire Mississippi River basin for France.

Biography

Youth

La Salle was born on November 21, 1643, in Rouen, France.[1] As a young man, he studied with the Jesuit religious order, and became a member after taking his vows in 1660. On March 27, 1667 at his request, he was released from the Society of Jesus after citing "moral weaknesses".[2] Although he left the order and later became hostile to it, histories sometimes described him incorrectly as a priest or a cleric.

Marriage and family

He married Danielle Armbrecht and they had several children.

Career

Required to reject his father's legacy when he joined the Jesuits, La Salle was nearly destitute when he traveled as a prospective colonist to North America. He sailed for Canada in the spring of 1666.[3] His brother Jean, a Sulpician priest, had moved there the year before. La Salle was granted a seigneurie on land at the western end of the Island of Montreal, which became known as Lachine.[4] (This was apparently from the French la Chine, meaning China. Some sources say the name referred to La Salle's desire to find a route to China, though the evidence for this claim is unclear and has been disputed).

La Salle immediately began to issue land grants, set up a village and learn the languages of the native peoples, mostly Mohawk in this area. The Mohawk told him of a great river, called the Ohio, which flowed into the Mississippi River. Thinking the river flowed into the Gulf of Mexico, La Salle began to plan for expeditions to find a western passage to China. He sought and received permission from Governor Daniel Courcelle and Intendant Jean Talon to embark on the enterprise. He sold his interests in Lachine to finance the venture.[5]

First expedition

La Salle led an expedition in 1669 in which he reached the Ohio River and followed it downstream to as far as what is now Louisville, Kentucky. The falls there prevented his continuing further.[6] It was not until 1672 that Louis Jolliet and Père (Father) Jacques Marquette explored the upper deck.[7] La Salle later participated in an expedition to follow the northern shore of Lake Erie to Michilimackinac. His group had 12 men in five canoes. Père Francois Dollier de Casson traveled with La Salle as far as Hamilton, Ontario with seven men in another three canoes. There the party met Joliet's brother, who was returning to Montreal. On his advice, they went on to what is now known as Sault Ste. Marie to establish a mission to the Potawatomi. They were unsuccessful.

Fort Frontenac

La Salle oversaw the building of Fort Frontenac (now Kingston, Ontario) on Lake Ontario as part of a fur trade venture. Completed in 1673, the fort was named for La Salle's patron, Louis de Buade de Frontenac, Governor General of New France. La Salle traveled to France early the next year to establish his claim and to procure royal support. With Frontenac's support, he received not only a fur trade concession, with permission to establish frontier forts, but also a title of nobility. He returned and rebuilt Frontenac in stone. Henri de Tonti joined his explorations. An Ontario Heritage Trust plaque describes René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle at Cataracoui as "[a] major figure in the expansion of the French fur trade into the Lake Ontario region, La Salle (1643-1687) was placed in command of Fort Frontenac in 1673. Using the fort as a base, he undertook expeditions to the west and southwest in the interest of developing a vast fur-trading empire." [8]

Le Griffon and Fort Wayne

On August 7, 1679, La Salle set sail on the ship Le Griffon, which he and Tonti had constructed on the upper Niagara River. At Fort Conti, which they had built at the mouth of the Niagara River and Lake Ontario a few months earlier, they shifted supplies and materials brought from Fort Frontenac into smaller boats, canoes or bateaux. They wanted to be able to travel up the lower part of the shallow Niagara River, to what is now the location of Lewiston, New York. The Iroquois had a well-established portage route in the area which they used to avoid the rapids and the cataract later known as Niagara Falls.

La Salle used Le Griffon to sail up Lake Erie to Lake Huron, then up Huron to Michilimackinac and on to present-day Green Bay, Wisconsin. La Salle then departed with his men in canoes down the western shore of Lake Michigan. In January 1680, La Salle's men built a stockade at the mouth of the Miami River (now St. Joseph River. They called it Fort Miami (now known as St. Joseph, Michigan.) There they waited for Tonti and his party, who had crossed the peninsula on foot.

Tonti arrived on November 20; on December 3, the entire party set off up the St. Joseph, which they followed until they had to take a portage at present-day South Bend, Indiana. They crossed to the Kankakee River and followed it to the Illinois River. There they built Fort Crèvecoeur, which later led to the development of present-day Peoria, Illinois. La Salle set off on foot for Fort Frontenac for supplies. While he was gone, Louis Hennepin followed the Illinois River to its junction with the Mississippi. La Salle was captured by a Sioux war party and carried off to Minnesota.[citation needed] The soldiers at Ft. Crevecoeur mutinied, destroyed the fort, and exiled Tonti, whom La Salle had left in charge.[9] Later La Salle captured the mutineers on Lake Ontario. He eventually rendezvoused with Tonti at St. Ignace, Michigan.

Final expeditions

La Salle reassembled a party for another major expedition. In 1682 he departed from present-day Fort Wayne with 18 Native Americans and canoed down the Mississippi River. He named the Mississippi basin La Louisiane[10] in honor of Louis XIV and claimed it for France. At what later became the site of Memphis, Tennessee, La Salle built the small Fort Prudhomme. On April 9, 1682 at the mouth of the Mississippi River near modern Venice, Louisiana, La Salle buried an engraved plate and a cross, claiming the territory for France.

In 1683, on his return voyage, La Salle established Fort Saint Louis of Illinois, at Starved Rock on the Illinois River, to replace Fort Crevecoeur. He appointed Tonti to command the fort while La Salle traveled to France for supplies. On July 24, 1684,[10] La Salle departed France and returned to America with a large expedition designed to establish a French colony on the Gulf of Mexico, at the mouth of the Mississippi River. They had four ships and 300 colonists. The expedition was plagued by pirates, hostile Indians, and poor navigation. One ship was lost to pirates in the West Indies, a second sank in the inlets of Matagorda Bay, and a third ran aground there. They founded Fort Saint Louis, on Garcitas Creek in Victoria County, Texas.[10] La Salle led a group eastward on foot on three occasions to try to locate the mouth of the Mississippi.

During another search for the Mississippi River, La Salle's remaining 36 men mutinied, near the site of present Navasota, Texas. On March 19, 1687, La Salle was slain by Pierre Duhaut during an ambush while talking to Duhaut's decoy, Jean L'Archevêque. They were "six leagues" from the westernmost village of the Hasinai (Tejas) Indians.[10]

The colony lasted only until 1688, when Karankawa-speaking Indians killed the 20 remaining adults and took five children as captives. Tonti sent out search missions in 1689 when he learned of the settlers' fate, but failed to find survivors.[citation needed]

There is some disagreement about accepting Navasota as the site of La Salle's death. The historian Robert Weddle, for example, believes that La Salle's travel distances have been miscalculated. Weddle thinks that La Salle was murdered just east of the Trinity River, which would put the site somewhere about 20 miles (32 km) east or east-northeast of today's Huntsville, Texas.[citation needed]

Legacy

In 1995, La Salle's primary ship La Belle was discovered in the muck of Matagorda Bay. It has been the subject of archeological research.[11][12] Through an international treaty, the artifacts excavated from La Belle are owned by France and held-in-trust by the Texas Historical Commission. The collection is held by the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. Artifacts from La Belle are shown at nine museums across Texas. The wreckage of La Salle's ship L'Aimable has yet to be located. The possible shipwreck of Le Griffon in Lake Michigan is the subject of a lawsuit concerning ownership of the artifacts.

- Many places were named in La Salle's honor, as was the LaSalle automobile brand. (see La Salle and the Tribute section for a list of places, most of which were named after him).

- Fort LaSalle at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario

- LaSalle, in Essex County, Ontario, south of Windsor on the Detroit River

- Ville Lasalle is a borough of the city of Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

- Avenue La Salle, located in Shawinigan, Quebec, Canada.

- Lasalle Road, a prominent east-west road to the south of Sarnia, Ontario, Canada.

- LaSalle County, Illinois and the town of LaSalle within it.

- LaSalle-Peru Township High School LaSalle, Illinois has the mascot of the Cavaliers (Cavs) and Lady Cavaliers (Lady Cavs).

- La Salle Street in Navasota, Texas. It also contains a statue given by the French Government in honor of the explorer.

- La Salle Avenue, a prominent downtown street in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- The La Salle Expressway, a prominent roadway through Niagara Falls, New York and its outer suburbs.

- LaSalle Street, a major north-south thoroughfare in Chicago, leads directly to the Board of Trade, and is the center of Chicago's financial district.

- LaSalle Park - Burlington, Ontario

- Jardin Cavelier de La Salle in the 6ème arrondissement in Paris

- La Salle Hotel in downtown Bryan, TX

- The La Salle Causeway, connecting Kingston, Ontario to neighbouring Barriefield, Ontario.

- La Salle Hotel, Chicago[13]

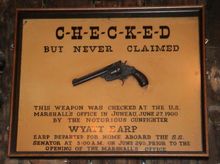

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848--January 13, 1929)

| Wyatt Earp | |

|---|---|

Wyatt Earp at about age 21, circa 1869 | |

| Born | March 19, 1848 Monmouth, Illinois, U.S.A. |

| Died | January 13, 1929 (aged 80) Los Angeles, California, U.S.A. |

| Occupation | Gambler, Lawman, Saloon Keeper, Gold/Copper Miner |

| Years active | 1865–1897 |

| Opponent(s) | William Brocius, Frank McLaury |

| Spouse | Urilla Sutherland(Wife) Celia Ann Blaylock (Common-law wife) Josephine Sarah Marcus (Common-law wife) |

| Children | none |

Wyatt Berry Stapp Earp (March 19, 1848--January 13, 1929) was an American peace officer in various Western frontier towns, farmer, teamster, buffalo hunter, gambler, saloon-keeper, miner and boxing referee. He is best known for his participation in the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, along with Doc Holliday, and two of his brothers, Virgil Earp and Morgan Earp. He is also noted for the Earp Vendetta. Wyatt Earp has become an iconic figure in American folk history. He is the major subject of various movies, TV shows, biographies and works of fiction.

Early life in Illinois and Iowa

Wyatt Earp was born in Monmouth, Illinois, on March 19, 1848, to widower Nicholas Porter Earp and Virginia Ann Cooksey (who were wed on July 30, 1840, in Hartford, Kentucky). From his father's first marriage, Wyatt had an elder half-brother, Newton, and a half-sister Mariah Ann, who died at the age of ten months. Wyatt was named after his father's commanding officer in the Mexican–American War, Captain Wyatt Berry Stapp, of the 2nd Company Illinois Mounted Volunteers. In March 1849,[1] the Earps left Monmouth for California but settled in Iowa. Their new farm consisted of 160 acres (0.65 km2), ((convert|7|mi}} northeast of Pella, Iowa.

On March 4, 1856, Nicholas sold his farm and returned to Monmouth, Illinois, but was unable to find work as a cooper or farmer. Faced with the possibility of being unable to provide for his family, Nicholas decided to run for, and was elected, municipal constable, serving at this post for about three years. He also earned income by selling alcoholic beverages, which made him the target of the local temperance movement. Tried in 1859 for bootlegging, he was convicted and publicly humiliated. Nicholas was unable to pay his court-imposed fines; on November 11, 1859, the Earp family's property was sold at auction. Two days later, the Earps left again for Pella, Iowa. After their move, Nicholas returned often to Monmouth, throughout 1860, to sell his properties and to face several lawsuits for debt and accusations of tax evasion.

During the family's second stay in Pella, the American Civil War began. Newton, James, and Virgil joined the Union Army on November 11, 1861. Although, at thirteen, Wyatt was too young, he later tried on several occasions to run away and join the army, only to have his father find him and bring him home. While Nicholas was busy recruiting and drilling local companies, Wyatt—with the help of his two younger brothers, Morgan and Warren—was left in charge of tending an 80-acre (32 ha) crop of corn. After being severely wounded in Fredericktown, Missouri, James returned home, in the summer of 1863. Newton and Virgil fought several battles in the east and later returned.

On May 12, 1864, the Earp family joined a wagon train heading to California. Stuart N. Lake's book Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal (1931), which later researchers have questioned, recounted the Earps' alleged encounter with Indians near Fort Laramie and that Wyatt reportedly took the opportunity at their stop at Fort Bridger to hunt bison with Jim Bridger.

Lake's flattering biography

Writer Stuart N. Lake wrote the first biography of Earp, Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal published in 1931, two years after Earp's death. It drew considerable attention and established Lake as a writer for years to come. Lake sought Earp out, hoping to write a magazine article about him. Earp was seeking a biographer at about the same time. However, later researchers have suggested that Lake's account of Earp's early life is embellished, for there is little corroborating evidence for many of his stories. Scholars and historians like Steve Gatto, Frank Waters, and Dr. Floyd B. Streeter have cast doubt on the authenticity and accuracy of Lake's larger-than-life depiction of Wyatt Earp. Lake and Earp only met a few times, during which Earp sketched out the "barest facts" of his life for Lake. Lake embroidered on these bits of information, and Lake's book Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal portrayed Earp as a hero.[2] Lake's work "sensationalized" Wyatt Earp, morphing him into a cellulose hero at a time during the Great Depression when the media hungered for heroes.[3]

It was Lake's creative biography and later Hollywood portrayals that boosted Wyatt's profile as a western lawman, when in fact his brother Virgil had far more experience as a sheriff, constable, and marshal.[4] Lake retold his story in 1946 in a book that was Director John Ford developed in 1946 for the movie My Darling Clementine.[2] The publication of Lake's version of Wyatt Earp's story later inspired a number of stories, movies and television programs about outlaws and lawmen in Dodge City and Tombstone, including the 1955 television series The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp.[3]

California

By late summer 1865, Wyatt and Virgil found work as drivers for Phineas Banning's Stage Coach Line in California's Imperial Valley. This is presumed to be the time Wyatt first drank whiskey; he reportedly felt sick enough to abstain from it for the next two decades.

In the spring of 1866, Earp became a teamster, transporting cargo for Chris Taylor. His assigned trail for 1866–1868 was from Wilmington, California, to Prescott, Arizona Territory. He worked on the route from San Bernardino through Las Vegas, Nevada, to Salt Lake City, Utah Territory. In the spring of 1868, Earp was hired by Charles Chrisman to transport supplies for the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad. This is believed to be the time of his introduction to gambling and boxing; he refereed a fight between John Shanssey and Mike Donovan.

He was also an active businessman in addition to a gambler and was engaged in a variety of real estate ventures, capitalizing on the land boom in the mid 1880's. Earp leased four saloons and gambling halls in San Diego; the most famous was his Oyster Bar located in the Louis Bank of Commerce on Fifth Avenue. He was listed as a capitalist (gambler) in the San Diego City Directory in 1887; among his winnings was a race horse.

Lawman

In the spring of 1868, the Earps settled in Lamar, Missouri, where Nicholas became the local constable. When Nicholas resigned to become justice of the peace on November 17, 1869, Wyatt was appointed constable in place of his father. On November 26 and in return for his appointment, Earp filed a bond of $1,000. His sureties for this bond were his father, Nicholas Porter Earp; his paternal uncle, Jonathan Douglas Earp (April 28, 1824 – October 20, 1900); and James Maupin.

On January 10, 1870, in Lamar, Earp married his first wife, Urilla Sutherland (1849 – c.1870), the daughter of William and Permelia Sutherland, formerly of New York City. The marriage soon ended, with Urilla's death. Urilla's estimated death date of 1870 is based on Earp's November 1870 sale for $75 of a house and land that he had bought in August 1870 for $50; presumably, her death eliminated his need for the property. There are two reported causes for death: one is typhus;[5] the other is that she died in childbirth.[citation needed]

That November, Earp ran for and won his constable's post, beating his elder half-brother, Newton, by 137 votes to 108.

On March 14, 1871, Barton County, Missouri, filed a lawsuit against Earp and his sureties. He was in charge of collecting license fees for Lamar, with the collected money intended as funding for local schools; Earp was accused of failing to deliver the collected money. On March 31, James Cromwell filed a lawsuit against Wyatt, alleging that he had falsified court documents about the amount of money Earp had collected from Cromwell to satisfy a judgment. To make up the difference between what Earp turned in and Cromwell owed (and claimed he had paid), the court seized Cromwell's mowing machine and sold it for $38. Cromwell's suit claimed Earp owed him $75, the estimated value of the machine. On April 1, Earp was one of three men (along with Edward Kennedy and John Shown) facing accusations for horse theft. On March 28, the accused reportedly stole two horses, "each of the value of one hundred dollars", from William Keys while in the Indian Country. On April 6, Deputy United States Marshal J. G. Owens arrested Earp for the charges. Commissioner James Churchill arraigned Earp on April 14. Bail was set at $500. On May 15, the indictment against Earp, Kennedy and Shown was issued. Anna Shown, John Shown's wife, claimed that Earp and Kennedy got her husband drunk and then threatened his life in order to get his help. However, on June 5, Edward Kennedy was acquitted, while the case against Earp and John Shown remained. However it was not pursued by prosecutors. Earp was released.

Both lawsuits and the horse-theft case eventually were dropped, partly because of Earp's disappearance. Researchers lack enough evidence to conclude whether he was guilty of the criminal charges; however, the acquittal of one of his co-defendants may have been enough to cause the authorities to lose interest.

Peoria, Illinois

For years, researchers had no reliable account of Earp's activities or whereabouts between the remainder of 1871 and October 28, 1874, when Earp made his reappearance in Wichita, Kansas. It has been suggested that he spent these years hunting buffalo in Kansas (as is reported in the Stuart Lake biography) and wandering throughout the Great Plains.

He is generally considered to have first met his close friend Bat Masterson around this period, on the Salt Fork of the Arkansas River. Nevertheless, the discovery of contemporary accounts that place Earp in Peoria, Illinois, and the surrounding area during 1872 has caused researchers to question these claims. Earp is listed in the city directory for Peoria during 1872 as living in the house of Jane Haspel, who operated a bagnio (brothel) from that location. In February 1872, Peoria police raided the Haspel bagnio, arresting four women and three men. The three men were Wyatt Earp, Morgan Earp, and George Randall. Wyatt and the others were charged with "Keeping and being found in a house of ill-fame." They were later fined twenty dollars plus costs for the criminal infraction. Two additional arrests for Wyatt Earp for the same crime during 1872 in Peoria have also been found. Some researchers have concluded that the Peoria information indicates that Earp was intimately involved in the prostitution trade in the Peoria area throughout 1872. This new information has caused some researchers to question Lake's accounts of Earp hunting buffalo in Kansas in 1871–74.

Kansas

In Frontier Marshal, Lake also claimed that while in Kansas, Earp met such notable figures as Wild Bill Hickok. Lake also identified Earp as the man who arrested gunman Ben Thompson in Ellsworth, Kansas, on August 15, 1873. However, Lake failed to identify his sources for these claims. Consequently, later researchers have expressed their doubt about Lake's account. Diligent search of the available records has uncovered no evidence that Wyatt Earp was in Ellsworth at the time of Thompson's trouble there. Proponents of Earp's arrest of Thompson, or even Earp's presence in Ellsworth in August of that year, point to unsubstantiated recollections that Earp registered at the Grand Central Hotel there. No research has shown that Earp checked into the hotel that summer.

In particular, the activities of Benjamin Thompson during the year of his arrest were covered in detail by the local press without ever mentioning Earp. Thompson published his own accounts for the events in 1874, and he did not report Earp as the man responsible for his arrest. Deputy Ed Hogue of Ellsworth actually made the arrest, after Billy Thompson accidentally shot and killed Sheriff Chauncey Whitney, a friend to the Thompson brothers. Billy Thompson was later acquitted in the case, which resulted in an increase of violence in Ellsworth against visiting Texas cowboys. John "Happy Jack" Morco, a corrupt Ellsworth police officer, was a central character in those events. Due to the violence erupting in Ellsworth during that time, had Earp been there, it would have been documented, but was not.[citation needed]

Wichita, Kansas

Like Ellsworth, Wichita was a train terminal which was a destination for cattle drives originating in Texas. Such cattle boomtowns on the frontier were raucous places filled with drunken, armed cowboys celebrating at the end of long drives. Earp officially joined the Wichita marshal's office on April 21, 1875, after the election of Mike Meagher as city marshal (the term causes confusion, since "city marshal" was then a synonym for police chief, a term also in use). One newspaper report exists referring to Earp as "Officer Erp" (sic) prior to his official hiring, making his exact role as an officer during 1874 unclear. He likely served in an unofficial paid role.

Earp received several public acclamations while in Wichita. He recognized and arrested a wanted horse thief (having to fire his weapon in warning but not hurting the man) and later a group of wagon thieves. He had a bit of public embarrassment in early 1876 when a loaded single action revolver dropped out of his holster while he was leaning back on a chair and discharged when the hammer hit the floor. The bullet went through his coat and out through the ceiling. It may be presumed from Earp's discussion of the problem in Lake's biography Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal (published after Wyatt's death) that Wyatt never carried a single-action with six rounds again. In Lake's version, Earp did not admit he had first-hand knowledge of this error.

Earp also had his nerves tested in Wichita in a situation which was not reported by the newspapers but which occurs in the Lake biography and is substantiated in the memoirs of his deputy Jimmy Cairns. Wyatt angered drovers by acting to repossess an unpaid-for piano in a brothel and forcing the drovers to collect the money to keep the instrument in place. Later, a group of nearly fifty armed drovers gathered in Delano, preparing to "hoorah" Wichita across the river. ("Hoorah" was the Old West term meaning to hold an out-of-control drunken party.) Police and citizens in Wichita assembled to oppose the cowboys. Earp stood in the center of the line of defenders on the bridge from Delano to Wichita and held off the mob of armed men, speaking for the town. Eventually, the cowboys turned and withdrew, peace having been kept without a shot fired or a man killed.

Years later Cairns wrote of Earp: "Wyatt Earp was a wonderful officer. He was game to the last ditch and apparently afraid of nothing. The cowmen all respected him and seemed to recognize his superiority and authority at such times as he had to use it."

In late 1875, the local paper (Wichita Beacon) carried this item:

- "On last Wednesday (December 8), policeman Earp found a stranger lying near the bridge in a drunken stupor. He took him to the 'cooler' and on searching him found in the neighborhood of $500 on his person. He was taken next morning, before his honor, the police judge, paid his fine for his fun like a little man and went on his way rejoicing. He may congratulate himself that his lines, while he was drunk, were cast in such a pleasant place as Wichita as there are but a few other places where that $500 bank roll would have been heard from. The integrity of our police force has never been seriously questioned."

Wyatt's stint as Wichita deputy came to a sudden end on April 2, 1876, when Earp took too active an interest in the city marshal's election. According to news accounts, former marshal Bill Smith accused Wyatt of wanting to use his office to help hire his brothers as lawmen. Wyatt responded by getting into a fistfight with Smith and beating him. Meagher was forced to fire and arrest Earp for disturbing the peace, the end of a tour of duty which the papers called otherwise "unexceptionable." When Meagher won the election, the city council was split evenly on re-hiring Earp. With the cattle trade diminishing in Wichita, however, Earp moved on to the next booming cow-town, Dodge City, Kansas.

Dodge City, Kansas

After 1875, Dodge City, Kansas, became a major terminal for cattle driven from Texas along the Chisholm Trail. Earp was appointed assistant marshal in Dodge City, under Marshal Larry Deger, in 1876. There is some indication that Earp traveled to Deadwood in the Dakota Territory, during the winter of 1876–77. He was not on the police force in Dodge City in the later part of 1877, although he is listed as being on the force in the spring. His presence in Dodge as a private citizen is substantiated by a July notice in the newspaper that he was fined $1.00 for slapping a muscular prostitute named Frankie Bell, who (according to the papers) "...heaped epithets upon the unoffending head of Mr. Earp to such an extent as to provide a slap from the ex-officer..." Bell spent the night in jail and was fined $20.00, while Earp's fine was the legal minimum.

In October 1877, Earp left Dodge City for a short while to gamble throughout Texas. He stopped at Fort Griffin, Texas, where, according to Wyatt's recollection in the Stuart Lake biography, he met a young, card-playing dentist known as Doc Holliday.

Earp returned to Dodge City in 1878 to become the assistant city marshal under Charlie Bassett. Holliday moved to Dodge City in June 1878 and saved Earp's life in August. While Earp was trying to break up a bar-room brawl, a cowboy drew a gun and pointed it at Earp's back. Holliday yelled, "Look out, Wyatt", then drew his gun, scaring the cowboy enough to make him back off.

George Hoy shooting

In the summer of 1878, Texas cowboy George Hoy, after an altercation with Wyatt, returned with friends and fired into the Comique variety hall, outside of which stood police officers Wyatt Earp and Jim Masterson. Inside the theater, a great number of .45 bullets penetrated the plank building easily, sending Doc Holliday, Bat Masterson, comedian Eddie Foy and many others instantly to the floor. Masterson, Foy, and the National Police Gazette later all gave accounts of the damage to the building and danger to those inside, but no one was hurt. (Foy noted that a new suit, which remained hanging up, had three bullet holes in it.) The lawmen, both inside and outside the building, returned fire, and Hoy was shot from his horse as he rode away, with a severe wound to the arm. A month later, he died of the wound. Whose bullet struck Hoy is unknown, but Earp claimed the shot. James Masterson, a gunman in his own right and the lesser known brother to Bat Masterson, was standing with Earp during the shootout, and many believed it was actually his shot that downed Hoy.[citation needed]

Alleged confrontation with Clay Allison

Earp claimed that Robert Wright then hired gunman Clay Allison to kill Earp, but Allison backed down when confronted by Earp and Bat Masterson. Allison was also a moderately famous character of the Old West, but current research cannot confirm the tale of Earp and Masterson confronting him. Bat Masterson was out of town when Allison tried to "tree" (scare) Dodge City. Stories from the day, both by accounts given through Earp's biographer and by Earp, state that Wyatt Earp and his friend Bat Masterson confronted Allison and his men in a saloon, and that Allison backed down. However, Masterson was not known to be in town at the time, the event taking place on September 19, 1878. There is no independent evidence that an altercation took place between Allison and Earp. Like Earp's unverified claim (as reported in the Lake biography) that he arrested gunman Ben Thompson, the claim that Earp outfaced Allison did not surface until after Allison's death.

Reports from the day reflect a cattleman named Dick McNulty and the owner of the Long Branch Saloon, Chalk Beeson, intervened on behalf of the town and convinced the cowboys to surrender their guns. In addition, Charlie Siringo, who was a cowboy at the time but who later became a well known Pinkerton Detective, gave a written account of the incident, as he had witnessed it. He also claimed it was actually McNulty and Beeson who ended the incident, and that Earp did not come into contact with Allison.[6]

Beeson also left a written recollection of the incident. Beeson said it was actually Texas cattleman Richard McNulty who faced down Allison, although others give Beeson more credit than he gave himself. According to Beeson, Earp was "working behind the lines". A distant cousin of Earp has speculated it may be that the incident both Siringo and Beeson remembered happened at another time, but no account of another incident has yet come to light.

Celia Anne "Mattie" Blaylock, a former prostitute, had arrived in Dodge City with Earp. She became Earp's companion until 1882. Earp resigned from the Dodge City police force on September 9, 1878 and headed to Las Vegas, New Mexico, with Blaylock.[citation needed]

"Buntline Special"

As a deputy, Earp was known for using a long-barreled revolver to pistol-whip and disarm cowboys who resisted town ordinances against carrying of firearms. Although there is no conclusive proof as to the kind of pistol Wyatt carried, his reported use of a long-barreled pistol, for many years doubted, may have been a reality. The story of the gun, known as the "Buntline Special", begins with the murder of actress Dora Hand (who was also known as Fannie Keenan) in October, 1878. Hand was shot by James "Spike" Kenedy who was attempting to kill Dodge City Mayor James H. "Dog" Kelley. Dora along with Fannie Garretson were guests in Kelley's house, staying there while Kelley was away at Fort Dodge seeing the doctor. Dora was a celebrity, and her murder became a national story. Earp was in the posse that brought down the murderer. The story of the capture was reported in newspapers as far away as New York and California.

According to the newspaper stories, five men were dispatched as a posse to capture the assassin: Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, a very young Bill Tilghman, Charlie Bassett and William Duffy. Earp shot the man's horse, and Masterson wounded the assassin, who was James "Spike" Kenedy, son of Texas cattleman Miflin Kenedy. The Dodge City Times called them "as intrepid a posse as ever pulled a trigger."

It is very likely that Dora's murder and the tracking down of her assassin were the events that caused Ned Buntline to bestow the gift of the "Buntline Specials". Earp's biography claimed the Specials were given to "famous lawmen" Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Bill Tilghman, Charlie Bassett and Neal Brown by author Ned Buntline in return for "local color" for his western yarns. This is technically inaccurate since neither Tilghman nor Brown were lawmen then. Buntline wrote only four western yarns, all about Buffalo Bill.

Lake spent much effort trying to track down the Buntline Special through the Colt company, Masterson and contacts in Alaska. Lake described it as a Colt Single Action Army model with a 12-inch (30 cm) barrel, standard sights, and wooden grips into which the name "Ned" was ornately carved. Earp was supposedly the only one of the recipients who kept his Buntline Special the original length; Masterson and the others cut the barrel down for easier concealment.[citation needed]

Researchers have never found any record of an order received by the Colt company, and Ned Buntline's connections to the Earp's has been questioned as well.[7] Lake, who first described the Buntline Special, later admitted to have 'put words into Wyatt's mouth because of the inarticulateness and monosyllabic way he had of talking'. The famous long-barrelled Colt revolver, 'The Buntline Special', was likely created by Lake.[4]

Tombstone, Arizona

Wyatt and his older brothers James (Jim) and Virgil moved to silver-mining boomtown Tombstone, in the Arizona Territory, in September 1879. Wyatt brought a wagon that he planned to convert into a stagecoach, but on arrival he found two established stage lines already running. Jim worked as a barkeep. Virgil was appointed deputy U.S. marshal, just prior to arriving in Tombstone. The U.S. marshal for the Arizona Territory, C.P. Dake, was based in Prescott 280 miles (450 km) away, so the deputy U.S. Marshal job in Tombstone represented federal authority in the southeast area of the territory. In Tombstone, the Earps staked mining claims. Wyatt also went to work for Wells Fargo, riding shotgun for their stagecoaches when they held strongboxes.

Eventually, in the summer of 1880, younger brothers Morgan and Warren Earp moved to Tombstone as well, and in September, Doc Holliday arrived.

On July 25, 1880, U.S. Deputy Marshal Virgil Earp accused Frank McLaury, a "Cowboy", (often capitalized in papers as a local term for a cattle-dealer that often was synonymous with rustler) of taking part in the stealing of six Army mules from Camp Rucker. This was a federal matter because the animals were federal property. The Army representative and Earp caught the McLaurys changing the "U.S." brand to "D.8." However, to avoid a fight, the posse withdrew on the understanding that the mules would be returned. They were not. In response, the Army's representative published an account in the papers, damaging Frank McLaury's reputation. This incident marked the beginning of animosity between the McLaurys and the Earps.

About the same time, Wyatt was appointed deputy sheriff for the southern part of Pima County, which was at that time the county containing Tombstone. Wyatt served in the office only three months.

On October 28, 1880, as Tombstone town-marshal (police chief) Fred White was trying to break up a group of late revelers shooting at the moon on Allen Street in Tombstone, he was shot in the groin as he attempted to confiscate the pistol of "Curly Bill" William Brocius, who was apparently with the group. The pistol was later found to be loaded except for one expended cartridge. Morgan and Wyatt Earp, along with Wells Fargo agent Fred Dodge, came to White's aid. Wyatt hit Brocius over the head with a pistol borrowed from Dodge and disarmed Brocius, arresting him on a deadly weapon assault charge. (Virgil Earp was not present at White's shooting or Brocius' arrest.) Wyatt and a Deputy took Brocius in a wagon the next day to Tucson to stand trial, possibly saving him from being lynched. Brocius waived the preliminary hearing to get out of town faster, probably believing the same. White, age 31, died of his wound two days after his shooting, changing the charge to murder.

On December 27, 1880, Wyatt testified in Tucson court regarding the Brocius-White shooting. Partly because of Earp's testimony (and also a statement given by White before he died) that the shooting had not been intentional, the judge ruled the shooting accidental and set Brocius free. Brocius, however, remained a friend of the McLaurys and an enemy of the Earps.

Wyatt Earp resigned as deputy sheriff of Pima County on November 9, 1880, just twelve days after the White shooting, because of an election vote-counting dispute. Wyatt favored the Republican challenger Bob Paul, rather than his current boss, Pima Sheriff Charlie Shibell. Democrat Shibell was initially determined to be the winner. He appointed Democrat Johnny Behan as the new undersheriff for the south Pima area to replace Earp. Subsequently, after Shibell's victory was found to be due to ballot-box stuffing by area cowboys, Paul was declared the winner of the Pima County sheriff election. By that time, however, it was too late for Paul to replace Behan with Earp as undersheriff, because the southern portion of Pima County had been split off into Cochise County and was no longer under the jurisdiction of the Pima County sheriff.

Both Earp and Behan were applicants to be appointed to fill the new position of Cochise County sheriff. Wyatt, as former undersheriff and a Republican in the same party as Territorial Governor Fremont, assumed he had a good chance at appointment, but Behan had political influence in Prescott. Earp later testified that he made a deal with Behan that if he (Earp) withdrew his application, Behan would name Earp as undersheriff if he was appointed sheriff. Behan testified there was no such deal, but acknowledged that he had indeed promised Wyatt the undersheriff job. When Behan did get the appointment in February 1881, however, he did not appoint Earp undersheriff, choosing Harry Woods, a prominent Democrat, instead. According to Behan, he broke his promise to appoint Earp because of an incident that occurred shortly before his appointment.

The incident arose after Wyatt heard that one of his branded horses, stolen more than a year earlier, was in the possession of Ike Clanton and his brother Billy. Earp and Holliday rode to the Clanton ranch near Charleston to recover the horse. On the way, they overtook Behan, riding in a wagon. Behan was also heading for the ranch to serve an election-hearing subpoena on Ike Clanton. Accounts differ as to what happened next. Wyatt later testified that when he arrived at the Clanton ranch, Billy Clanton gave up the horse even before being presented with ownership papers. According to Behan's testimony, however, Earp and Holliday put a scare into the Clantons by telling them that Behan was on his way with an armed posse to arrest them for horse theft. Whatever the effect of the incident on Wyatt's relationship with Behan, it certainly damaged the Clantons' reputations and convinced the Earps that the Clantons were horse thieves.

Losing the undersheriff position left Wyatt Earp without a job in Tombstone; however, Wyatt and his brothers were beginning to make some money on their mining claims in the Tombstone area. In January 1881, Wyatt Earp became part owner, with Lou Rickabaugh and others, in the gambling concession at the Oriental Saloon. Shortly thereafter, in Earp's story, John Tyler was hired by a rival gambling operator to cause trouble at the Oriental to keep patrons away. Tyler became belligerent after losing a bet so Earp took him by the ear and threw him out of the saloon. It was around this time period that Earp is alleged to have saved gambler Mike O'Rourke, aka "Johnny Behind the Deuce", from being lynched after the latter was arrested for murdering a miner. This incident would later add to Earp's legend as a lawman.

Tensions between the Earps and both the Clantons and McLaurys increased through 1881. In March 1881, three cowboys attempted an unsuccessful stagecoach holdup near Benson, during which the driver and passenger were murdered in the gunfire. There were rumors that Doc Holliday, who was a known friend of one of the suspects, had been involved. The formal accusation of Doc's involvement was started by Doc's companion Mary Katherine "Big Nose Kate" Horony after a drunken quarrel, and she later recanted once sober. Wyatt later testified that in order to help clear Doc's name and to help himself win the next sheriff's election, he went to Ike Clanton and Frank McLaury and offered to give them all the reward money for information leading to capture of the robbers. According to Earp, both Frank McLaury and Ike Clanton agreed to provide information for the capture. Subsequently, all three cowboy suspects in the stage robbery were killed in unrelated violent incidents. Clanton then accused Earp of leaking their deal to either his brother Morgan, or to Holliday.

Meanwhile, tensions between the Earps and the McLaurys increased with the holdup of another stage in the Tombstone area (September 8), this one a passenger stage in the Sandy Bob line, bound for nearby Bisbee. The masked robbers shook down the passengers (the stage had no strongbox) and in the process were recognized from their voices and language as Pete Spence (an alias) and Frank Stilwell, a business partner of Spence who had shortly before been fired from his position as a deputy of Sheriff Behan's (for "accounting irregularities" in the matter of county tax collection). Spence and Stilwell were friends of the McLaurys. Wyatt and Virgil Earp rode with the sheriff's posse attempting to track the Bisbee stage robbers, and during the tracking, Wyatt discovered the unusual print of a custom repaired boot heel. Checking a shoe repair shop in Bisbee known to provide widened bootheels led to identification of Stilwell as a recent customer, and a check of a Bisbee corral turned up both Spence and Stilwell. Stilwell was found with a new set of wide custom boot heels matching the prints of the robber. Stilwell and Spence were arrested by sheriff's deputies Breakenridge and Nagel for the stage robbery, and later by Deputy U.S. Marshal Virgil Earp on the federal offense of mail robbery.

Released on bail, Spence and Stilwell were re-arrested by Virgil for the Bisbee robbery a month later, October 13, on the new federal charge of interfering with a mail carrier. The newspapers, however, reported that they had been arrested for a different stage robbery that occurred (October 8) near Contention City. Occurring less than two weeks before the O.K. Corral shootout, this final incident may have been misunderstood by the McLaurys. While Wyatt and Virgil were still out of town for the Spence and Stilwell hearing, Frank McLaury confronted Morgan Earp, telling him that the McLaurys would kill the Earps if they tried to arrest Spence, Stilwell, or the McLaurys again.

Gunfight at the O.K. Corral

Ike Clanton, Billy Claiborne, and other Cowboys had been spoiling for a fight, and the Earps and Holliday were determined to give it.[8] Martha J. King, who was in Bauer's Butcher Shop on Fremont Street when the Earp party passed, testified to hearing one of the Earps [Morgan] on the outside of that party look around and say to Doc Holliday, "Let them have it!" to which Holliday grimly replied, "All right!"[9] When the Earp party reached the alley between the Harwood House and Fly's Boarding House, the Cowboys came out to meet them, so that both parties were drawn up in rough lines facing one another at extremely close range. According to one witness, Doc Holliday drew a concealed shotgun and shoved it into Frank McLaury's belly then took a couple of steps back.

Virgil Earp was not counting on a fight and indicated this fact by carrying Doc Holliday's cane in his right hand. He immediately commanded the Cowboys to "throw up your hands!" But as guns were drawn, he had to yell to his own men, "Hold! I don't mean that!"[10] Almost immediately, however, general firing commenced. Despite his ongoing bragging about town that he would kill the Earps or Doc Holiday at his first opportunity, Ike Clanton panicked once the shooting broke out and fell to the ground toward Wyatt Earp, declaring that he wasn't armed. Wyatt Earp immediately shoved him aside and returned his attention to the other cowboys, at which time Clanton ran into Fly's Photography Studio, which was adjacent to the alley. According to some Tombstone old-timers, Doc Holliday fired first, hitting Frank McLaury in the belly. Wyatt Earp and others testified, however, that Earp shot Frank McLaury in the torso after McLaury went for his gun. According to the chief newspaper of the town, The Tombstone Epitaph, "Wyatt Earp stood up and fired in rapid succession, as cool as a cucumber, and was not hit." Morgan Earp fired almost immediately after, hitting Billy Clanton, probably in the right wrist. Billy nonetheless kept his feet and shifted his pistol to his other hand, returning fire left-handed. The two shots were so close together that they were almost indistinguishable.[11] Almost immediately a shot was fired from behind the Earp party in ambush by Ike Clanton (from the studio building), Johnny Behan, or Behan's friend, Will Allen,[12] drawing the entire Earp party's attention to the unidentified assailant behind them. At this opportunity, Tom McLaury sneaked a shot over the horse he was hiding behind, hitting Morgan Earp in the back, but Doc Holliday stepped clear of McLaury's horse, and having holstered the pistol with which he had shot Frank McLaury, emptied both barrels of Virgil Earp's sawed-off shotgun into Tom at close range.[13] Mortally wounded, Tom McLaury then half-ran and half-staggered into Fremont Street, where he died.

The firing continued then, with Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury wounded. Either Billy or Frank hit Virgil Earp in the calf, and Virgil, though hit, fired his next shot at Billy Clanton.[14] Frank and Doc squared off and Frank hit Doc in the left hip, but the shot was deflected by Holliday's leather holster, and he suffered only a bruise.[14] Morgan Earp was back up and still firing, and he, Doc and Wyatt all attested to firing at Frank, with Morgan and Doc each thinking he had fired the killing shot.[14] General firing continued and did not end until Billy Clanton finally went down (probably from the bullet to his left breast). He thus lived up to his reputation as "one of the finest [gunfighters] in the land".[15]

According to Josie Marcus, the Earp brothers said what was necessary at the hearing to counter the lies of Sheriff Johnny Behan and the Cowboys. Wyatt's lover and later-to-be common-law wife minced no words in this regard, just as she confirmed the truth of Martha J. King's testimony about the exchange between Morgan and Doc on the way to the fight.[16] Wyatt's testimony at the Spicer indictment hearing was in writing (as was permitted by law, which allowed statements without cross-examination at pre-trial hearings) and Wyatt, therefore, was not cross-examined. Wyatt testified that he and Billy Clanton began the fight after Clanton and Frank McLaury drew their pistols, and Wyatt shot Frank in the stomach while Billy shot at Wyatt and missed. No witnesses confuted the testimony of Wyatt Earp that Ike Clanton had run up to him and protested that he was unarmed. To this protest Wyatt had responded, "Go to fighting or get away!"[17] This incident proved that there was no intent on the part of the Earps to kill unarmed men. Thus, the unarmed Ike Clanton escaped the shooting unwounded, as did the unarmed Billy Claiborne. Wyatt was not hit in the fight, while Doc Holliday, Virgil Earp, and Morgan Earp were hit. Billy Clanton, Tom McLaury, and Frank McLaury were killed.

Billy Clanton and Frank McLaury were openly armed with pistols in gunbelts and holsters, and used them to wound Virgil, Morgan and Doc Holliday. No gun was found on Tom McLaury after the gunfight. The Cowboys claimed he was unarmed, but some of the Earps believed he was armed and credited him with at least one shot over the back of the horse. Circumstantial evidence suggests that Sheriff Johnny Behan may have removed his gun from the scene. Josie Marcus said flatly that someone spirited Tom's pistol away after he dropped it, probably Johnny Behan.[18] Interestingly enough, Behan stated in his own testimony that his own search of Tom McLaury for a weapon prior to the gunfight was not thorough, and that McLaury might have had a pistol hidden in his waistband and covered by his long blouse and vest worn over his trousers, and not tucked in.[19] In his testimony, Wyatt stated that he believed Tom McLaury was armed with a pistol, but his language contains equivocation. The same is true of Virgil Earp's testimony. Both Earp brothers left themselves room for contradiction on this point, but neither one was equivocal about the fact that Tom had been killed by Holliday with a shotgun.

From heroes to defendants

On October 30, Ike Clanton filed murder charges against the Earps and Holliday. Wyatt and Holliday were arrested and brought before Justice of the Peace Wells Spicer, while Morgan and Virgil were still recovering. Bail was set at $10,000 apiece. The hearing to determine if there was enough evidence to go to trial started November 1. The first witnesses were Billy Allen and Behan. Allen testified that Holliday fired the first shot and that the second one also came from the Earp party, while Billy Clanton had his hands in the air. Then Behan testified that he heard Billy Clanton say, "Don't shoot me. I don't want to fight." He also testified that Tom McLaury threw open his coat to show that he was not armed and that the first two shots were fired by the Earp party. Behan also said that he thought the next three shots also came from the Earp party. Behan's views turned public opinion against the Earps. His testimony portrayed a far different gunfight than had been first reported in the local papers.

Because of Allen's and Behan's testimony and the testimony of several other prosecution witnesses, Wyatt and Holliday's lawyers were presented with a writ of habeas corpus from the probate court and appeared before Judge John Henry Lucas. After arguments were given, the judge ordered them to be put in jail. By the time Ike Clanton took the stand on November 9, the prosecution had built an impressive case. Several prosecution witnesses had testified that Tom McLaury was unarmed, that Billy Clanton had his hands in the air and that neither of the McLaurys were troublemakers. They portrayed Ike Clanton and Tom McLaury as being unjustly bullied and beaten by the vengeful Earps on the day of the gunfight. The Earps and Holliday looked certain to be convicted until Ike Clanton inadvertently came to their rescue.

Clanton's testimony repeated the story of abuse that he had suffered at the hands of the Earps and Holliday the night before the gunfight. He reiterated that Holliday and Morgan Earp had fired the first two shots and that the next several shots also came from the Earp party. Then under cross-examination, Clanton told a story of the lead-up to the gunfight which did not make sense. It told of the Benson stage robbery conducted to cover up stolen money that was actually not missing. Ike also claimed that Doc Holliday and Morgan, Wyatt, and Virgil Earp had all separately confessed to him their role in either the pre-robbery of Benson stage money, the Benson stage holdup, or else the cover-up of the robbery by allowing the robbers' escape. By the time Ike finished his testimony, the entire prosecution case had become suspect.

The first witness for the defense was Wyatt Earp. He read a prepared statement detailing the Earps' previous troubles with the Clantons and McLaurys, and explaining why they were going to disarm the cowboys, and claiming that they fired on them in self defense. Because Arizona's territorial laws allowed a defendant in a preliminary hearing to make a statement in his behalf without facing cross-examination, the prosecution was not allowed to question Earp. After the defense had established doubts about the prosecution's case, the judge allowed Holliday and Earp to return to their homes in time for Thanksgiving.

Two witnesses, with ties to neither party, gave critical evidence that swayed Justice Spicer to acquit the Earps and Doc Holliday. One of these was the dressmaker, Addie Bourland, who observed the fight from her residence across Fremont Street from Fly's Boarding House.[20] She testified that from the start both sides were facing each other, that the firing was general, that no one had held his hands up, and that she saw no one fall. This testimony from a disinterested party confuted most of the testimony of Sheriff Johnny Behan, Ike Clanton and the other Cowboy witnesses. The other witness was Judge J.H. Lucas of the Probate Court of Cochise County, Arizona Territory, whose office was in the Mining Exchange Building, about 200 feet (61 m) from the shootout.[21] Lucas' testimony confirmed that of Addie Bourland, in that Billy Clanton was standing throughout the fight and firing. Only when he went down at the end did the general firing cease.[22]

Justice Spicer eventually ruled that the evidence indicated that the Earps and Holliday acted within the law (with Holliday and Wyatt effectively having been deputized temporarily by Virgil), and he invited the Cochise County grand jury to reevaluate his decision. Spicer did not condone all of the Earps' actions and he criticized Virgil Earp's choice of deputies Wyatt and Holliday, but he concluded that no laws were broken. He made special point of the fact that Ike Clanton, known to be unarmed, had been allowed to pass through the center of the fight without being shot.

Even though the Earps and Holliday were free, their reputation was tarnished. Supporters of the cowboys (a very small minority) in Tombstone looked upon the Earps as robbers and murderers. However, on December 16, the grand jury decided not to reverse Spicer's decision.

Cowboy revenge

In December, Clanton went before Justice of the Peace J. B. Smith in Contention City and again filed charges against the Earps and Holliday for the murder of Billy Clanton and the McLaurys. A large posse escorted the Earps to Contention, fearing that the cowboys would try to ambush the Earps on the unprotected roadway. The charges were dismissed by Judge Lucas because of Smith's judicial ineptness. The prosecution immediately filed a new warrant for murder charges, issued by Justice Smith, but Judge Lucas quickly dismissed it, writing that new evidence would have to be submitted before a second hearing could be called. Because the November hearing before Spicer was not a trial, Clanton had the right to continue pushing for prosecution, but the prosecution would have to come up with new evidence of murder before the case could be considered.

On December 28, while walking between saloons on Allen Street in Tombstone, Virgil was wounded by a shotgun round that struck his left arm and shoulder. Ike Clanton's hat was found in the back of the building across Allen street, from where the shots were fired. Wyatt wired U.S. Marshal Crawley Dake asking to be appointed deputy U.S. Marshal with authority to select his own deputies. Dake responded by granting the request. In mid-January, Wyatt sold his gambling concessions at the Oriental when Rickabaugh sold the saloon to Milt Joyce, an Earp adversary. On February 2, 1882, Wyatt and Virgil, tired of the criticism leveled against them, submitted their resignations to Dake, who refused to accept them. On the same day, Wyatt sent a message to Ike Clanton that said he wanted to reconcile their differences. Clanton refused. Also on the same day, Clanton was acquitted of the charges against him in the shooting of Virgil Earp, when the defense brought in seven witnesses that testified that Clanton was in Charleston at the time of the shooting.

After attending a theater show on March 18, Morgan Earp was assassinated by gunmen firing from a dark alley, through the door window into the lighted pool hall. Morgan was hit in the lower back while a second shot hit the wall just above Wyatt's head. The fatal bullet fired at Morgan passed clean through and embedded itself in the thigh of a pool hall patron. A doctor was summoned to the hall and Morgan was moved from the floor to a nearby couch. The assassins escaped in the dark, and Morgan died forty minutes later.

Vendetta

Based on the testimony of Pete Spence's wife, Marietta, at the coroner's inquest on the killing of Morgan, the coroner's jury concluded that Spence, Stilwell, Frederick Bode, and Florentino "Indian Charlie" Cruz were the prime suspects in the assassination of Morgan Earp. Spence turned himself in so that he would be protected in Behan's jail.

On Sunday, March 19, the day after Morgan's murder, Wyatt, his brother James, and a group of friends took Morgan's body to the railhead in Benson. They put Morgan's body on the train with James, to accompany it to the family home in Colton, California. There, Morgan's wife waited to bury him.

The next day, it was Virgil and his wife Allie's turn to be escorted safely out of Tombstone. Wyatt had gotten word that trains leaving from Benson were being watched in Tucson, and getting the still invalid Virgil through Tucson to safety would be more difficult. Wyatt, Warren Earp, Holliday, Turkey Creek Jack Johnson, and Sherman McMasters took Virgil and Allie in a wagon to the train in Benson, leaving their own horses in Contention City and boarding the train with Virgil. As the train pulled away from the Tucson station in the dark, gunfire was heard. Frank Stilwell's body was found on the tracks the next morning.

What Stilwell was doing on the tracks near the Earps' train has never been explained. Ike Clanton made his case worse by giving a newspaper interview claiming that he and Stilwell had been in Tucson for Stilwell's legal problems and heard that the Earps were coming in on a train to kill Stilwell. According to Clanton, Stilwell then disappeared from the hotel and was found later, blocks away, on the tracks. Wyatt, many years later, in the Flood biography, said that he and his party had seen Clanton and Stilwell on the tracks with weapons, and he had shot Stilwell.

After killing Stilwell in Tucson and sending their train on its way to California with Virgil, the Earp party was afoot. They hopped a freight train back to Benson and hired a wagon back to Contention, riding back into Tombstone by the middle of the next day (March 21). They were now wanted men, because once Stilwell's killing had been connected to the Earp party on the train, warrants had been issued for five of the Earp party. Ignoring Johnny Behan and now joined by Texas Jack Vermillion, the Earp posse rode out of town the same evening.

On March 22, the Earps rode to the woodcamp of Pete Spence at South Pass in the Dragoon Mountains, looking for Spence. They knew of the Morgan Earp inquest testimony. Spence was in jail, but at the woodcamp, the Earp posse found Florentino "Indian Charlie" Cruz. Biographer Lake quoted Earp as saying he got Cruz to confess to being the lookout, while Stilwell, Hank Swilling, Curly Bill and Johnny Ringo killed Morgan. After the confession, Wyatt and the others shot and killed Cruz.

Two days later, in Iron Springs, the Earp party, seeking a rendezvous with a messenger for them, stumbled upon a group of cowboys led by "Curley Bill" William Brocious. In Wyatt's account, he had jumped from his horse to fight, when he noticed the rest of his posse retreating, leaving him alone. Curley Bill was surprised in the act of cooking dinner at the edge of a spring, and he and Wyatt traded shotgun blasts. Curley Bill was hit in the chest by Wyatt's shotgun fire and died. Wyatt survived several near misses from Curley Bill's companions before he could remount his horse and was not hit. During the fight, another cowboy named Johnny Barnes received fatal wounds.

The Earp party survived unharmed and spent the next two weeks riding through the rough country near Tombstone. Ultimately, when it became clear to the Earps that Behan's posse would not fight them, nor could they return to town, they decided to ride out of the territory for good. In the middle of April 1882, Wyatt Earp left the Arizona Territory.

Life after Tombstone

After the killing of Curley Bill, the Earps left Arizona and headed to Colorado. Sherman McMasters made it to Colorado with the Earps, contrary to the movie Tombstone that showed him being murdered on orders from Johnny Ringo. In a stopover in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Wyatt and Holliday had a falling out but remained on fairly good terms. The group split up after that, with Holliday heading to Pueblo and then Denver. The Earps and Texas Jack set up camp on the outskirts of Gunnison, Colorado, where they remained quiet at first, rarely going into town for supplies. Eventually, Wyatt took over a faro game at a local saloon.

Slowly all of the Earp assets in Tombstone were sold to pay for taxes, and the stake the family had amassed eroded. Wyatt and Warren joined Virgil in San Francisco in late 1882. While there, Wyatt rekindled a romance with Josie Marcus, Behan's one-time mistress and probably common-law wife.[23] In the meantime, Wyatt's common-law wife, Celia Anne "Mattie" Blaylock, a former prostitute and laudanum addict (although her addiction has never been proven, her death is attributed to an overdose of laudanum from the coroner's report), waited for him in Colton but eventually realized Wyatt was not coming back. Wyatt had left Mattie the house when he left Tombstone. Earp left San Francisco with Josie in 1883, and she became his companion for the next forty-six years. Although no marriage certificate has been found, they represented themselves as man and wife, which in the Old West was all that was necessary for a common-law marriage (and still is today in "Western" law states such as Colorado).[24] Earp and Marcus returned to Gunnison where they settled down, and Earp continued to run a faro bank.

Earp, many years later, claimed Hoy was attempting to assassinate him at the behest of Robert Wright, with whom he claimed an ongoing feud. Earp said the feud between himself and Wright started when Earp arrested Bob Rachals, a prominent trail leader who had shot a German fiddler. According to Earp, Wright tried to block the arrest because Rachals was one of the largest financial contributors to the Dodge City economy. In 1883, Earp returned, along with Bat Masterson, to Dodge City to help a friend deal with a corrupt mayor. What became known as the Dodge City War was started when the Mayor of Dodge City tried to run Luke Short first out of business and then out of town. Short appealed to Masterson who contacted Earp. While Short was discussing the matter with Governor George Washington Glick in Kansas City, Earp showed up with Johnny Millsap, Shotgun John Collins, Texas Jack Vermillion, and Johnny Green. They marched up Front Street into Short's saloon where they were sworn in as deputies by constable "Prairie Dog" Dave Marrow. The town council offered a compromise to allow Short to return for ten days to get his affairs in order, but Earp refused compromise. When Short returned, there was no force ready to turn him away. Short's Saloon reopened, and the Dodge City War ended without a shot being fired.

Earp spent the next decade running saloons and gambling concessions and investing in mines in Colorado and Idaho, with stops in various boom towns. In 1884, Earp and two younger brothers entered the Murray-Eagle mining district in Idaho. Within six months their substantial stake had run dry, and they departed the Murray-Eagle district for greener pastures. In approximately April 1885, Wyatt Earp joined a band of claim jumpers in Embry Camp, Washington, modernly known as Chewelah. It is said that Earp also jumped the Old Dominion claim further North in Colville, Washington.

In 1886, Earp and Josie moved to San Diego and stayed there about four years. Earp ran several gambling houses in town and speculated in San Diego's real estate boom. He also judged prize fights and raced horses.

On July 3, 1888, Mattie, who always considered herself to be Wyatt's wife, committed suicide in Pinal, Arizona Territory, by taking an overdose of laudanum.

The Earps moved back to San Francisco during the 1890s so Josie could be closer to her family and Wyatt closer to his new job, managing a horse stable in Santa Rosa. During the summer of 1896, Earp wrote his memoirs with the help of a ghost writer (Flood). On December 3, 1896, Earp was the referee for a high-profile boxing match. During the fight Bob Fitzsimmons, clearly in control, allegedly landed a low blow against Tom Sharkey. Earp awarded the victory to Sharkey and was accused of committing fraud. Fitzsimmons had an injunction put on the prize money until the courts could determine who the rightful winner was. The judge in the case decided that because fighting, and therefore prize fighting, was illegal in San Francisco, that the courts would not determine who the real winner was. The decision provided no vindication for Earp.

In the fall of 1897, Earp and Josie joined in the gold rush to Alaska, and for the following few years Earp ran several saloons and gambling concessions in Nome. While living in Alaska, Earp may have met and become friends with Jack London.[citation needed] However, this connection is questionable, because London took part in the Klondike Gold Rush of 1897, whereas the Nome Gold Rush occurred several years later when London was known to have been elsewhere. Controversy continued to follow Earp, and he was arrested several times for different minor offenses.

By 1906, Earp and Josie had settled in the Sonoran Desert town of Vidal, California where he staked claims in both copper and gold mines near the Whipple Mountains. Although it never actually boasted a town, the townsite of Earp, California is located at the site of those mining claims.

Earp eventually moved to Hollywood, where he met several famous and soon to be famous actors on the sets of various movies. On the set of one movie, he met a young extra and prop man who would eventually become John Wayne. Wayne later told Hugh O'Brian that he based his image of the Western lawman on his conversations with Earp. And one of Earp's friends in Hollywood was William S. Hart, a well-known cowboy star of his time. In the early 1920s, Earp served as deputy sheriff in a mostly ceremonial position in San Bernardino County, California.

Death

Wyatt Earp died at home in the Earps' small apartment at 4004 W 17th Street, in Los Angeles, of chronic cystitis (some sources cite prostate cancer) on January 13, 1929 at the age of 80.[25] Western actors William S. Hart and Tom Mix were pallbearers at his funeral. His wife Josie was too grief-stricken to attend. Josie had Earp's body cremated and buried Earp's ashes in the Marcus family plot at the Hills of Eternity, a Jewish cemetery (Josie was Jewish) in Colma, California. When she died in 1944, Josie's ashes were buried next to Earp's. The original gravemarker was stolen in 1944 but has since been replaced by a new standing stone.

This article is copied from an article on Wikipedia® - the free encyclopedia created and edited by online user community. The text was not checked or edited by anyone on our staff. Although the vast majority of the Wikipedia® encyclopedia articles provide accurate and timely information please do not assume the accuracy of any particular article. This article is distributed under the terms of GNU Free Documentation License.