Developing Your Organization's Future Leaders

Imagine that several mid-level managers in your organization are planning to retire in the next few months, and, as a result, you're facing a serious staffing problem.

Do you start searching outside your organization, or should you focus on finding people from within the company, so that you can quickly train them for these positions?

Many organizations spend a lot of time searching for good people for their leadership teams. It's often most efficient to promote from within, as internal people are "known quantities," and are already familiar with how the company works.

However, many organizations don't have a process in place for "growing their own leaders," so they need to search for outside talent to bring in.

In this article, we'll look at the Leadership Pipeline Model, a tool that helps you plan for internal leadership development. We'll then look at how you can apply this model to your organization.

About the Model

Ram Charan, Stephen Drotter, and James Noel developed the Leadership Pipeline Model, based on 30 years of consulting work with Fortune 500 companies. They published the model in their 2000 book, "The Leadership Pipeline," which they revised in 2011.

The model helps organizations grow leaders internally at every level, from entry level team leaders to senior managers. It provides a framework that you can use to identify future leaders, assess their competence, plan their development, and measure results. Put simply, you can use the model to think about how you'll train your people to take the next step up the leadership ladder.

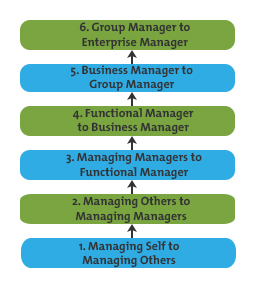

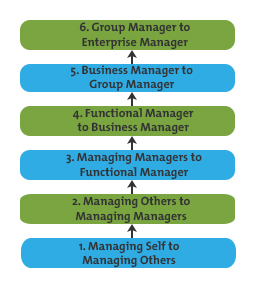

According to the model's developers, leaders progress through six key transitions, or "passages," in order to succeed. These six leadership transitions are show in Figure 1, below.

Figure 1 – The Leadership Pipeline Model

Each leadership stage needs different skill-sets and values, and, at each transition, leaders have to develop these in order to lead successfully.

According to the model, senior leaders in the organization should mentor more junior managers through each leadership transition, to ensure that they're using the appropriate skills for their current level. Staying "stuck" without the right skills, even if the manager progresses upward, can cause leaders to stagnate, become ineffective, and, ultimately, fail.

Uses of the Model

There are several benefits of using the Leadership Pipeline Model.

First, promoting leaders from within is better than searching for outside talent. These outside leadership stars often flit from one organization to the next, looking for the best opportunities, and leaving the organizations they have finished with to fill the gaps. The model's "pipeline" ensures that organizations have a steady stream of internal candidates qualified for open leadership roles.

The Leadership Pipeline encourages leaders to develop new skills and mind-sets for leading at the next level, rather than reverting to those used at the previous level, and this increases their flexibility and effectiveness.

If an organization's culture focuses on developing existing employees, this can raise the morale of the entire workforce. When people see opportunities to advance, staff turnover goes down and productivity and engagement go up. Furthermore, the investment in development pays off, because professionals stay with the organization longer.

As well as being useful for organizations that want to develop the next generation of leaders internally, this model is also helpful for planning your own career trajectory. Because you can identify the skills and approaches that you'll need for each transition, you can start to prepare yourself for your next promotion.

Applying the Model

Let's look at the six transitions in the Leadership Pipeline Model, and discuss how you can prepare people to make these transitions successfully.

1. From Managing Self to Managing Others

When someone is transitioning from working independently to managing others, a significant change in attitude and skill set must take place. The new leader is now responsible for getting work done through others â€" a drastically different style of working.

To manage others successfully, these leaders must share information, offer autonomy, be aware of people's needs, and provide direction.

Navigating This Transition

Organizations need to make sure that first-time managers understand what's required of them.

New leaders need to focus on their communications skills, and communicate effectively with their teams. Partly, this involves communicating clearly in writing, but it can also be as simple as making time for subordinates to discuss their concerns. They need to know how to plan short- and long-term goals, define work objectives, and manage conflicting priorities.

New managers must also focus on their team members' needs. Coach new managers to practice Management by Wandering Around, which helps them stay in touch with their people. Encourage them to provide feedback, so that everyone on the team can improve.

It's important for new managers to know how to delegate effectively. At this level they're responsible for other people, and, if they can't delegate, they'll be harried, overworked, and stressed. This will also harm your organization's ability to get work done quickly.

Last, if you're coaching new managers through this transition, make sure that you monitor their progress to help them navigate the process successfully. Sit in on their interactions with direct reports, consider using 360° feedback to see how others view their abilities as a manager, and help them address any issues that arise.

2. From Managing Others to Managing Managers

This transition often presents a dramatic jump in the number of hands-on professionals that the manager is responsible for, which means that a number of new skills and working values are needed.

Navigating This Transition

First, new managers at this level need to know how to hold level one managers accountable. This might include becoming a coach or mentor to help them develop, and providing appropriate training. Managers in level two are also responsible for training the managers in level one, so make sure that they're aware of available training resources, and ensure that they know how to develop effective training sessions.

At level one, new managers might know how to get people to work together to accomplish a goal. But, at level two, managers must have the knowledge and skills needed to build an effective team.

Finally, these managers need to know how to allocate resources to the people and teams below them. These resources could be money, technology, time, or support staff, and they need to know how to budget effectively. They must know how to identify teams or units that are wasting resources, as well as knowing where to apply additional resources to improve performance.

3. From Managing Managers to Functional Manager

Functional managers often report to the business's general manager, and they are responsible for entire departments, such as manufacturing or IT. Making a transition to this level requires a great deal of maturity, and the ability to build connections with other departments.

Navigating This Transition

Functional managers must learn how to think strategically and manage with the entire department, or function, in mind.

Leaders at this level must know how to think over the long-term, as they'll need to plan for the medium-term future. They must also understand the organization's long-term goals, so that their functional strategy aligns with these aims.

Coach new functional managers to stay up-to-date on industry trends, so that they can take advantage of new advances: managers who are aware of technology and trends can adjust their strategy to better contribute to the organization's competitive advantage.

Although all managers need to be good listeners, this skill is particularly important at functional manager level. Teach your functional managers how to use active listening skills. They also need to be skilled at reading body language, so that they can avoid misinterpretation and spot untruths.

4. From Functional Manager to Business Manager

This transition may be the most challenging of the six leadership passages, because these professionals have to change the way that they think. When you're managing a business, complexity is high, the position is very visible, and many business managers receive little guidance from senior leaders.

Business managers oversee all of the functions of a business, not just one, and this requires a shift in values and perception.

Navigating This Transition

New business managers have to adjust their thinking to focus on future growth in all areas of the organization. They need to understand each function of the organization and know how these functions interrelate. Without this understanding, business managers will likely only focus on one or two functions, which could damage the organization's growth.

Encourage new business managers to get to know their functional managers well – for example, by talking with them and taking them on important trips; this will allow them to get to know the decision makers in each function and help them understand each function's value to the organization.

This group needs to know about the organization's core business processes, and understand where the profit lies within these processes. Without this knowledge, business managers can make costly strategic mistakes.

Last, and this isn't as trivial as it may seem, business managers need excellent time management skills. Managers who lack these skills won't spend enough time on key projects or with key people, so make sure that this group knows how to focus on important, not just urgent, tasks.

5. From Business Manager to Group Manager

To be a successful group manager, another subtle shift in skills must take place. At this level, managers are responsible for individual businesses which are often dispersed around the world. They must have the ability to get these businesses working together to accomplish the broader organization's long-term goals and objectives.

Navigating This Transition

Group managers need the ability to value others' success, and they must be humble enough to help others succeed. They need to learn how to critique the business managers' strategy-formulation, and provide effective feedback.

Group managers should know how to create the right mix of investments in their businesses to help the organization succeed. Resource allocation, market prediction and segmentation, and global business etiquette are all important skills here.

They also need to stay on top of all of their businesses to ensure that they're obeying the law, sticking to corporate policy, acting in a way that's consistent with corporate strategy, enhancing the global brand, and making a robust profit.

The businesses in their group that show the most promise in all these areas are the ones that will be fully funded. So, group managers must know how to maintain good relationships with businesses, even if they aren't getting the funding they want. They also need analytical skills in order to balance what's good for their businesses, versus what's good for the organization.

6. From Group Manager to Enterprise Manager

The enterprise manager, or CEO, is on the final rung of the career ladder for managers. This is the most visible position in the company; after all, if the CEO fails, it influences how people perceive the organization.

Navigating This Transition

Future CEOs need to understand that once they ascend to this level, they're responsible for a number of different stakeholder groups and organizations, such as the board, financial analysts, investors, partners, the workforce, direct reports, and local communities. Failing any of these groups means a loss of credibility.

By the time that managers reach this stage, they should already have developed many of the leadership skills mentioned in this article. However, there are several ways in which they can develop further. Our article on Level 5 Leadership teaches good leaders how to become great leaders by developing humility.

Often, CEOs, because of their number of responsibilities, have to make good decisions under an incredible amount of pressure. Make sure that potential leaders are familiar with a wide range of decision-making techniques, and know how to think on their feet.

Last, risk taking is a given at this level, but future CEOs need the courage to take calculated risks, even when they face opposition from others. This requires character, integrity, decisiveness, and inner strength.

Key Points

Ram Charan, Stephen Drotter, and James Noel developed the Leadership Pipeline Model and published it in their book, "The Leadership Pipeline." The model highlights six progressions that managers can go through as they develop their careers.

These progressions are from:

- Managing self to managing others.

- Managing others to managing managers.

- Managing managers to functional manager.

- Functional manager to business manager.

- Business manager to group manager.

- Group manager to enterprise manager.

While organizations can use these progressions to help develop their people, individuals can also use them to grow personally, increasing their knowledge and skills so that they're ready for their next promotion.