The Copyright Act of 1790 was the first federal copyright act to be instituted in the United States, though most of the states had passed various legislation securing copyrights in the years immediately following the Revolutionary War. The stated object of the act was the "encouragement of learning," and it achieved this by securing authors the "sole right and liberty of printing, reprinting, publishing and vending" the copies of their "maps, charts, and books" for a term of 14 years, with the right to renew for one additional 14 year term should the copyright holder still be alive.

Early Developments

The 1709 British Statute of Anne did not apply to the American colonies, although some scholars have asserted otherwise. The colonies' economy was largely agrarian, hence copyright law was not a priority, resulting in only three private copyright acts being passed in America prior to 1783. Two of the acts were limited to seven years, the other was limited to a term of five years. In 1783 several authors' petitions persuaded the Continental Congress "that nothing is more properly a man's own than the fruit of his study, and that the protection and security of literary property would greatly tends to encourage genius and to promote useful discoveries." But under the Articles of Confederation, the Continental Congress had no authority to issue copyright, instead it passed a resolution encouraging the States to "secure to the authors or publishers of any new book not hitherto printed... the copy right of such books for a certain time not less than fourteen years from the first publication; and to secure to the said authors, if they shall survive the term first mentioned,... the copy right of such books for another term of time no less than fourteen years.[1] Three states had already enacted copyright statutes in 1783 prior to the Continental Congress resolution, and in the subsequent three years all of the remaining states except Delaware passed a copyright statute. Seven of the States followed the Statute of Anne and the Continental Congress' resolution by providing two fourteen year terms. The five remaining States granted copyright for single terms of fourteen, twenty and twenty one years, with no right of renewal.[2]

The Act

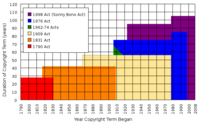

At the Constitutional Convention 1787 both James Madison of Virginia and Charles Pinckney of South Carolina submitted proposals that would allow Congress the power to grant copyright for a limited time. These proposals are the origin of the Copyright Clause in the United States Constitution, which allows the granting of copyright and patents for a limited time to serve a utilitarian function, namely "to promote the progress of science and useful arts". The first federal copyright act, the Copyright Act of 1790 granted copyright for a term of "fourteen years from the time of recording the title thereof", with a right of renewal for another fourteen years if the author survived to the end of the first term. The act covered not only books, but also maps and charts. With exception of the provision on maps and charts the Copyright Act of 1790 is copied almost verbatim from the Statute of Anne.[3]

The Copyright Act of 1790 was deliberated on and passed during the Second Session of Congress, convened on January 4, 1790. The bill was signed into law on May 31, 1790 by George Washington, and published in its entirety throughout the country shortly after. At only half a page in the Columbia Centinel [1], a Boston newspaper of the day, the law was considerably shorter than current statutes, which, as of 2003, totalled some 279 pages. The law covered only books, maps, and charts; paintings, drawings, and music were not included until later.[citation needed]

Provisions

Much of the Act was borrowed from the 1709 British Statute of Anne. The first sentences of the two laws are almost identical. Both require registration in order for a work to receive copyright protection; similarly, both require that copies of the work be deposited in officially designated repositories such as the Library of Congress in the United States, and the Oxford and Cambridge universities in the United Kingdom. The Statute of Anne and the Copyright Act of 1790 both provided for an initial term of 14 years, renewable once by living authors for an additional 14 years, for works not yet published. The Statute of Anne differed from the 1790 Act, however, in providing a 21-year term of protection, with no option for renewal, for works already published at the time the law went into effect (1710).[citation needed]

Geographic Reach

The Copyright Act of 1790 applied exclusively to citizens of the United States. Non-citizens and material printed outside the United States could not be granted any copyright protection until the International Copyright Act of 1891. Consequently, Charles Dickens sometimes complained about cheap American knockoffs of his work for which he received no royalty. The first significant challenge to this law came in the case of Wheaton v. Peters, decided in 1834.[citation needed]

Federal Law

At the time works only received protection under federal statutory copyright if the statutory formalities, such as a proper copyright notice, were satisfied. If this was not the case the work immediately entered into the public domain. In 1834 the Supreme Court ruled in Wheaton v. Peters, a case similar to the British Donaldson v Beckett of 1774, that although the author of an unpublished work had a common law right to control the first publication of that work, the author did not have a common law right to control reproduction following the first publication of the work.[4]

Thanks to Encyclopedia The Free Dictionary / Farlex, Inc.

http://encyclopedia.thefreedictionary.com/p/Copyright%20Act%20of%201790

| To Get Uninterrupted Daily Article(s) / Review(s) Updates; Kindly Subscribe To This BlogSpot:- http://ZiaullahKhan.Blogspot.com/ Via "RSS Feed" Or " Email Subscription" Or "Knowledge Center Yahoo Group". | ||

| Amazon Magazine Subscriptions | Amazon Books | Amazon Kindle Store |

| Amazon Everyday Low Prices, Sales, Deals, Bargains, Discounts, Best-Sellers, Gifts, Household Consumer Products | ||